- AKTUALNOŚCI

- NARODOWY POZP 2017-2022

- MODEL ORGANIZACYJNY ŚWIAT

- MODEL ORGANIZACYJNY DB

- KONTAKT

-

ARCHIWUM

-

PODKARPACKI POZP 2017-2022

>

- Aktualności do 2020

- Forum PK 2017-2018

- KONGRES ZP 2017 Sesja ZP DZIECI

- Forum PK 2016 Dzieci i Młodzież

-

NPOZP 2015 kalendarium

>

- 2015 V-IX wystąpienia

- 20150527 Apel Porozumienia na Rzecz NPOZP

- 20150729 Komunikat prasowy

- 20150801 Ekspertyza prof. Jacka Wciórki

- 20150804 Wystąpienie do Marszałka Sejmu

- 20150806 Interpelacja Posła Józefa Lasoty

- 20150813 List otwarty

- 20150820 Wspólne stanowisko

- 20150821 Ekspertyza Regina Bisikiewicz

- 20150821 Ekspertyza - załącznik RB

- 20150903 Apel Porozumienia na Rzecz NPOZP

- 20150911 Oświadczenie po głosowaniu

- 20150922 Opinia o Raporcie za 2014

- Forum PK 2014 XII Rzeszow

- Forum PK 2014 V Stalowa Wola >

- RPO 2014 Raport streszczenie

- Forum PK 2013

- Interwencja 2013 redukcja łóżek w Rzeszowie

- Konferencja PK 2012 ZP DZIECI

- PkPOZP 2012-2016

- NPOZP 2007-2015 >

-

PODKARPACKI POZP 2017-2022

>

-

EKONOMIKA ZDROWIA PSYCHICZNEGO

- EZP01 Teoria ekonomiczna w zarysie

- EZP02 Rys historyczny systemu KCh iNFZ

- EZP08 Rachunek kosztów działań ABC

- EZP03 Jakość i efektywność

- EZP12 Program pilotażowy - wytyczne i ocena

- EZP05 Opieka koordynowana

- EZP06 Opieka stopniowalna

- EZP04 JGP

- EZP07 Zarządzanie populacyjne

- EZP09 Wielka Brytania commissioning & payment

- EZP10 USA utilizatian & payment

- EZP11 Niemcy cost-effectiveness

- EZP13 Włochy

- EZP14

- EZP15

- EZP16

- Standardy Holandia

- Standardy Australia

- Standardy Niemcy

- Standardy Włochy

- Standardy Anglia

- UK OPIEKA ŚRODOWISKOWA

- UK OPIEKA STACJONARNA

- UK STANDARDY NICE

- Debata medialna o pilotażu CZP

THE INITIAL PSYCHIATRIC INTERVIEW

Robert Waldinger M.D.

Alan M. Jacobson M.D.

WSTĘPNY WYWIAD PSYCHIATRYCZNY (tłumaczenie Google)

Robert Waldinger

Alan M.Jacobson

1 .Jakie są główne cele pierwszego wywiadu psychiatrycznego?

Postawienie wstępnej diagnostyki różnicowej i sformułowanie planu leczenia. Cele te osiąga się poprzez:

Zbieranie informacji:

■ Dojście do empatycznego zrozumienia, jak czuje się pacjent. To zrozumienie jest podstawą do nawiązania relacji z pacjentem.

Kiedy klinicysta uważnie słucha, a następnie wyraża uznanie dla zmartwień i trosk pacjenta, pacjent zyskuje poczucie, że jest rozumiany. To poczucie bycia zrozumianym jest podstawą całego późniejszego leczenia i pozwala klinicyście zainicjować związekw którym można zawrzeć sojusz na rzecz leczenia.

2. To dużo, na czym należy się skupić podczas pierwszego spotkania. A pomoc pacjentowi?

Wstępna diagnoza i plan leczenia mogą być szczątkowe. Rzeczywiście, gdy pacjenci są w kryzysie, historia może być niejasna, niekompletna lub zawężona. W rezultacie niektóre interwencje są podejmowane nawet wtedy, gdy zbierane są podstawowe informacje o

historii, relacjach rodzinnych i obecnych stresorach. Bardzo ważne jest, aby pamiętać, że trudności emocjonalne często powodują izolację. Doświadczenie dzielenia się swoim problemem

z zatroskanym słuchaczem może samo w sobie przynieść ogromną ulgę. Tak więc wstępny wywiad jest początkiem leczenia jeszcze przed ustaleniem formalnego planu leczenia.

3. Jak powinna być zorganizowana rozmowa wstępna?

Nie ma jednego ideału, ale warto pomyśleć o wstępnej rozmowie zgłoszeniowej jako składającej się z trzech elementów:

Nawiąż wstępny kontakt z pacjentem i zapytaj o zgłaszaną skargę lub problemy, czyli o to, co sprowadziło pacjenta na pierwsze spotkanie. Niektórzy pacjenci opowiadają swoje historie bez większych wskazówek ze strony klinicysty, podczas gdy inni wymagają wyraźnych instrukcji w formie konkretnych pytań, które pomogą im uporządkować myśli. Podczas tej fazy pierwszego wywiadu pacjent powinien mieć jak najwięcej możliwości podążania za własnymi schematami myślowymi.

Uzyskaj określone informacje, w tym historię prezentowanych problemów, istotne informacje medyczne, pochodzenie rodzinne, historię społeczną oraz określone objawy i wzorce zachowań. Formalnie przetestuj stan psychiczny (patrz ten rozdział).

Zapytaj, czy pacjent ma jakieś pytania lub o których nie wspomniał obawy. Następnie pacjent otrzymuje wstępne zalecenia dotyczące dalszej oceny i/lub rozpoczęcia leczenia.

Chociaż te trzy części wywiadu można rozpatrywać oddzielnie, często przeplatają się one ze sobą, np. obserwacje stanu psychicznego można prowadzić od momentu spotkania klinicysty z pacjentem.

Stosowny wywiad medyczny i rodzinny może zostać przywołany w trakcie przedstawiania innych obaw, a pacjenci mogą zadawać ważne pytania dotyczące zaleceń dotyczących leczenia, gdy przedstawiają swój początkowy wywiad.

4. Czy wstępna ocena różni siew przypadku złożonych sytuacji?

Wstępna ocena psychiatryczna może wymagać więcej niż jednej sesji w złożonych sytuacjach - na przykład podczas oceny dzieci lub rodzin lub oceny przydatności pacjenta do określonego podejścia terapeutycznego, takiego jak krótka psychoterapia. Wstępna ocena może również wymagać zebrania informacji z innych źródeł: rodziców, dzieci, współmałżonka, najlepszego przyjaciela, nauczyciela, funkcjonariuszy policji i/lub innych pracowników służby zdrowia. Kontakty te mogą zostać włączone do pierwszej wizyty lub mogą wystąpić później. Pierwszym krokiem w dokonywaniu takich usta leń jest wyjaśnienie pacjentowi powodu ich zawarcia oraz uzyskanie wyraźnej, pisemnej zgody na kontakt.

5. Jak należy podejść do źródła skierowań?

Prawie zawsze właściwe jest skontaktowanie się ze źródłem skierowania w celu zebrania informacji i wyjaśnienia wstępnych wrażeń diagnostycznych i planów leczenia. Wyjątki mogą wystąpić, gdy skierowanie pochodzi od innych pacjentów, przyjaciół lub innych osób niebędących profesjonalistami, których pacjent chce wykluczyć z leczenia.

6. Czy istnieją jakieś odmiany tych wytycznych dla wstępnej oceny?

Konkretne orientacje teoretyczne mogą dyktować istotne różnice w wstępnej ocenie. Na przykład terapeuta behawioralny kieruje dyskusję do konkretnych analiz bieżących problemów i poświęca niewiele czasu na doświadczenia z wczesnego dzieciństwa. Ocena psychofarmakologiczna kładzie nacisk na specyficzne wzorce objawów, reakcje na wcześniejsze leczenie farmakologiczne oraz występowanie chorób psychicznych w rodzinie. Podejście przedstawione w tym rozdziale jest zestawem zasad o szerokim zastosowaniu, które można zastosować w ocenie większości pacjentów.

7. W jaki sposób zbierane są informacje z wywiadu?

Klinicysta musi dowiedzieć się jak najwięcej o tym, jak pacjent myśli i czuje. Podczas wywiadu klinicznego zbierane są informacje z tego, co pacjent mówi klinicyście; krytycznie ważne wskazówki pochodzą również z tego, jak rozwija się historia. Zatem zarówno treść wywiadu (tj. to, co mówi pacjent), jak i przebieg wywiadu (tj. sposób, w jaki pacjent to mówi) oferują ważne drogi do zrozumienia problemów pacjenta. Weź pod uwagę kolejność przekazywanych informacji, komfort mówienia o nich, emocje związane z dyskusją, reakcje pacjenta na pytania i wstępne uwagi, spójność prezentacji oraz czas podania informacji. Pełne opracowanie takich informacji może zająć jedną lub kilka sesji w ciągu dni, tygodni lub miesięcy, ale podczas pierwszego wywiadu można zasugerować głębsze obawy.

Na przykład 35-letnia kobieta zgłosiła zaniepokojenie nawracającą astmą jej syna i związanymi z tym trudnościami w szkole. Swobodnie mówiła o swoich obawach i zasięgała rady, jak pomóc synowi. Zapytana o myśli męża, na chwilę się uspokoiła. Następnie powiedziała, że podziela jej obawy i przeniosła dyskusję z powrotem na jej syna. Jej wahanie wskazywało na inne problemy, które pozostały nierozwiązane podczas pierwszej sesji. Rzeczywiście, zaczęła kolejną sesję od pytania: „Czy mogę mówić o czymś innym niż o moim synu?". Uspokoiwszy się, opisała chroniczną złość męża na syna z powodu jego „słabości". Jego złość i jej własne uczucia w odpowiedzi stały się ważnym celem późniejszego leczenia.

8. Jak należy rozpocząć rozmowę zgłoszeniową?

Tu i teraz jest miejscem, w którym zaczyna się wszystkie wywiady. Można zadać jedno z wielu prostych pytań: „Co cię dzisiaj do mnie sprowadza? Możesz mi powiedzieć, co cię trapi?Jak

Czy to dlatego, że zdecydowałeś się umówić na to spotkanie? W przypadku niespokojnych pacjentów przydatna jest struktura: wczesne zapytanie o wiek, stan cywilny i sytuację życiową może dać im czas na stanie się czują się komfortowo, zanim przystąpią do opisu swoich problemów. Jeśli lęk jest ewidentny, prosty komentarz na temat lęku może pomóc pacjentom porozmawiać o swoich zmartwieniach.

9. Czy wysoce ustrukturyzowany format jest ważny?

Nie. Pacjenci muszą mieć możliwość uporządkowania swoich informacji w sposób, który im najbardziej odpowiada. Klinicysta, który przedwcześnie poddaje pacjenta strumieniowi konkretnych pytań, ogranicza informacje o własnym procesie myślowym pacjenta, nie uczy się, jak pacjent radzi sobie z ciszą lub smutkiem, odcina mu możliwość podpowiedzi lub wprowadzenia nowych tematów.

Ponadto zadanie polegające na formułowaniu jednego konkretnego pytania po drugim może zakłócać zdolność lekarza do słuchania i rozumienia pacjenta.

Nie oznacza to, że należy unikać konkretnych pytań. Często pacjenci udzielają rozbudowanych odpowiedzi na konkretne pytania, takie jak „Kiedy byłeś żonaty?" Ich odpowiedzi mogą otworzyć nowe możliwości dochodzenia. Kluczem jest unikanie szybkiego podejścia i umożliwienie pacjentom rozwinięcia myśli.

10. Jak należy zadawać pytania?

Pytania powinny być formułowane w sposób zachęcający pacjentów do rozmowy. Pytania otwarte, które nie wskazują odpowiedzi, zwykle pozwalają ludziom rozwinąć więcej niż pytania szczegółowe lub naprowadzające. Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, pytania naprowadzające (np. „Czy czułeś się smutny, kiedy twoja dziewczyna się wyprowadziła?") mogą przeszkadzać w rozmowie, ponieważ mogą sprawiać wrażenie, że osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad oczekuje od pacjenta pewnych uczuć. Niewiodące pytania („Jak się czułeś, kiedy twoja dziewczyna się wyprowadziła?") są równie bezpośrednie i skuteczniejsze.

11. Jaki jest skuteczny sposób radzenia sobie z wahaniami pacjentów?

Kiedy pacjenci potrzebują pomocy w opracowaniu, proste stwierdzenie i/lub prośba mogą wywołać więcej informacji: „Opowiedz mi o tym więcej". Powtarzanie lub zastanawianie się nad tym, co mówią pacjenci, również zachęca ich do otwarcia się (np. „Mówiłeś o swojej dziewczynie"). Czasami komentarze, które konkretnie odzwierciedlają zrozumienie przez lekarza odczuć pacjenta w związku ze zdarzeniami, mogą pomóc pacjentowi rozwinąć temat. Takie podejście zapewnia potwierdzenie zarówno klinicyście, jak i pacjentowi, że nadają na tych samych falach. Gdy klinicysta prawidłowo zareaguje na ich odczucia, pacjenci często potwierdzają odpowiedź poprzez dalszą dyskusję. Pacjent, którego dziewczyna odeszła, może czuć się zrozumiany i swobodniej rozmawiać o stracie po komentarzu typu „Wydajesz się zniechęcony wyprowadzką swojej dziewczyny".

12. Podaj przykład, jak kompleksowe gromadzenie informacji może wskazać problem.

Starszy mężczyzna został skierowany z powodu narastającego przygnębienia. W pierwszym wywiadzie opisał najpierw trudności finansowe, a następnie poruszył niedawny rozwój problemów medycznych, których kulminacją była diagnoza raka prostaty. Kiedy zaczął mówić o raku i chęci poddania się, zamilkł. W tym momencie wywiadu klinicysta wyraził uznanie, że pacjent wydawał się być przytłoczony narastającymi problemami finansowymi i, w większości, wszystko, medyczne zmiany. Pacjent cicho skinął głową, a następnie rozwinął swoje szczególne obawy dotyczące tego, jak jego żona będzie sobie radzić po jego śmierci. Nie czuł, że jego dzieci będą jej pomocne. Nie było jeszcze jasne, czyjego pesymizm odzwierciedlał depresyjną nadmierną reakcję na diagnozę raka, czy też dokładną ocenę rokowania. Dalsza ocena objawów i stanu psychicznego oraz krótka rozmowa z żoną w dalszej części spotkania wykazały, że rokowania są całkiem dobre. Następnie leczenie koncentrowało się na jego depresyjnych reakcjach na diagnozę.

13. Jak najlepiej formułować pytania?

Klinicysta powinien używać języka, który nie jest techniczny ani nadmiernie intelektualny. Jeśli to możliwe, należy używać własnych słów pacjenta. Jest to szczególnie ważne w przypadku spraw intymnych, takich jak problemy seksualne. Ludzie opisują swoje doświadczenia seksualne w dość zróżnicowanym języku. Jeśli pacjent mówi, że jest gejem, użyj dokładnie tego terminu, a nie pozornie równoważnego terminu, takiego jak homoseksualista. Ludzie używają niektórych słów, a innych nie, ze względu na specyficzne konotacje, jakie niosą dla nich różne słowa; na początku takie rozróżnienia mogą nie być oczywiste dla klinicysty.

14. A co z pacjentami, którzy nie są wstanie porozumiewać się w spójny sposób?

Klinicysta musi przez cały czas być świadomy tego, co dzieje się podczas wywiadu. Jeśli pacjent ma halucynacje lub jest bardzo zdenerwowany, nieuznanie zdenerwowania lub niepokojącego doświadczenia może zwiększyć niepokój pacjenta.

Omówienie aktualnego zdenerwowania pacjenta pomaga złagodzić napięcie i mówi pacjentowi, że lekarz słucha. Jeśli historia pacjenta jest chaotyczna lub niejasna, uznaj trudności w zrozumieniu pacjenta i oceń możliwe przyczyny (np. psychoza z poluzowanymi skojarzeniami vs. lęk przed wizytą).

Kiedy pytania ogólne (np. „Opowiedz mi coś o swoim pochodzeniu") są nieskuteczne, może być konieczne zadawanie szczegółowych pytań dotyczących rodziców, szkoły i dat wydarzeń. Pamiętaj jednak, że zadawanie niekończących się pytań w celu złagodzenia własnego niepokoju, a nie pacjenta, może być kuszące.

15. Podsumuj kluczowe punkty, o których należy pamiętać podczas pierwszego wywiadu.

Umożliwienie pacjentowi swobodnego opowiedzenia własnej historii musi być zrównoważone poprzez uwzględnienie zdolności pacjenta do skupienia się na istotnych tematach. Niektóre osoby wymagają wskazówek od klinicysty, aby uniknąć zagubienia się w stycznych tematach. Inni mogą potrzebować spójnej struktury, ponieważ mają problemy z uporządkowaniem myśli, być może z powodu wysokiego stopnia niepokoju. Empatyczny komentarz na temat niepokoju pacjenta może go zmniejszyć, a tym samym doprowadzić do wyraźniejszej komunikacji.

Niektóre wytyczne dotyczące rozmowy zgłoszeniowej

• Pozwól, aby pierwsza część wstępnego wywiadu podążała za tokiem myślenia pacjenta.

• Zapewnij strukturę, aby pomóc pacjentom, którzy mają problemy z uporządkowaniem myśli lub dokończeniem uzyskiwania określonych danych.

• Formułuj pytania, aby zachęcić pacjenta do rozmowy (np. pytania otwarte, nienaprowadzające).

• Używaj słów pacjenta.

• Bądź wyczulony na wczesne oznaki utraty kontroli nad zachowaniem (np. wstawanie do tempa).

• Zidentyfikuj mocne strony pacjenta oraz obszary problemowe.

• Unikaj żargonu i technicznego języka.

• Unikaj pytań zaczynających się od „dlaczego".

• Unikaj przedwczesnych zapewnień.

• Nie pozwalaj pacjentom zachowywać się niewłaściwie (np. łamać lub rzucać przedmiotami).

• postaw granice wobec wszelkich zagrażających zachowań i w razie potrzeby wezwij niezbędną pomoc.

16. Jakich konkretnych pułapek należy unikać podczas wstępna rozmowa zgłoszeniowa?

Unikaj żargonu lub terminów technicznych, chyba że jest to jasno wyjaśnione i konieczne. Pacjenci mogą używać żargonu, na przykład: „Miałem paranoję". Jeśli pacjent używa słowa technicznego, zapytaj o jego znaczenie. Możesz być zaskoczony zrozumieniem pacjenta. Na przykład pacjenci mogą używać słowa „paranoik", aby zasugerować strach przed dezaprobatą społeczną lub pesymizm co do przyszłości. Uważaj również, aby podczas wywiadu przypisać problemom pacjenta etykietę diagnostyczną. Pacjent może być przestraszony i zdezorientowany etykietą.

Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, unikaj zadawania pytań zaczynających się od „dlaczego". Pacjenci mogą nie wiedzieć, dlaczego mają określone doświadczenia lub uczucia i mogą czuć się nieswojo, a nawet głupio, jeśli uważają, że ich odpowiedzi nie są „dobre". Pytanie dlaczego oznacza również, że oczekujesz od pacjenta szybkich wyjaśnień.

Pacjenci dowiadują się więcej o źródłach swoich problemów, zastanawiając się nad swoim życiem podczas wywiadu i kolejnych sesji. Kiedy masz ochotę zapytać dlaczego, sformułuj pytanie tak, aby wywołało bardziej szczegółową odpowiedź.

Alternatywy obejmują „Co się stało?" „Jak to się stało?" lub „Co o tym myślisz?'

Unikaj przedwczesnej pewności siebie. Kiedy pacjenci są zdenerwowani, jak to często bywa podczas pierwszych wywiadów, osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad może ulec pokusie, by rozwiać obawy pacjenta, mówiąc: „Wszystko będzie dobrze" lub „Nie ma tu nic naprawdę złego".

Jednak zapewnienie jest prawdziwe tylko wtedy, gdy klinicysta (1) dokładnie zbadał charakter i zakres problemów pacjenta oraz (2) jest pewien tego, co mówi pacjentowi. Przedwczesne zapewnienie może zwiększyć niepokój pacjenta, sprawiając wrażenie, że lekarz wyciągnął pochopne wnioski bez dokładnej oceny lub po prostu mówi to, co pacjent chce usłyszeć. Pozostawia również pacjentów samych ze swoimi obawami oto, co naprawdę jest nie tak.

Co więcej, przedwczesne zapewnienia raczej zamykają dyskusję niż zachęcają do dalszych badań problem. Bardziej uspokajające może być zapytanie pacjenta, co go niepokoi. Proces (tj. charakter interakcji) pociesza pacjenta bardziej niż jakakolwiek pojedyncza rzecz, którą może powiedzieć klinicysta.

Postaw granice zachowaniom.

Z powodu problemów psychiatrycznych niektórzy pacjenci mogą stracić kontrolę nad sesją. Chociaż opisane tutaj podejście kładzie nacisk na pozwolenie pacjentowi na kierowanie dużą częścią werbalnej dyskusji, czasami należy wyznaczyć granice niewłaściwego zachowania. Pacjenci, którzy są podnieceni i chcą się rozebrać lub grożą, że rzucą przedmiotem, muszą być kontrolowani.

Cel ten najczęściej osiąga się poprzez komentowanie narastającego pobudzenia, omawianie go, dopytywanie o źródła niepokoju i informowanie pacjentów o granicach akceptowalnego zachowania. W rzadkich przypadkach pomoc z zewnątrz może być konieczna (np. ochroniarze na oddziale ratunkowym), zwłaszcza jeśli zachowanie się nasila, a przesłuchujący wyczuwa niebezpieczeństwo. Wywiad należy przerwać do czasu, gdy zachowanie pacjenta będzie można opanować w taki sposób, aby można było bezpiecznie kontynuować.

17. O czym często zapomina się w ocenie pacjentów?

Nowy pacjent nawiązuje kontakt z klinicystą z powodu problemów i zmartwień; to są uzasadnione pierwsze tematy wywiadu. Pomocne jest również zrozumienie mocnych stron pacjenta, które są podstawą, na której będzie opierać się leczenie. Mocne strony obejmują sposoby, w jakie pacjent z powodzeniem radził sobie z przeszłym i obecnym cierpieniem, osiągnięciami, źródłami wewnętrznej wartości, przyjaźniami, osiągnięciami w pracy i wsparciem rodziny. Mocne strony obejmują również hobby i zainteresowania, które pacjenci wykorzystują do walki ze swoimi zmartwieniami.

Pytania typu „Z czego jesteś dumny?" lub „Co lubisz w sobie?" może ujawnić takie informacje.

Często informacje wychodzą po namyśle w trakcie rozmowy. Na przykład jeden pacjent był bardzo dumny ze swojej wolontariatu w kościele. Wspomniał o tym tylko mimochodem, omawiając swoje zajęcia na tydzień przed spotkaniem. Jednak ta praca wolontariacka była jego jedynym aktualnym źródłem osobistej wartości. Zwrócił się do niego, gdy zdenerwował się brakiem sukcesów w karierze.

18. Jaka jest rola humoru w wywiadzie?

Pacjenci mogą używać humoru, aby odwrócić rozmowę od tematów wywołujących lęk lub niepokojących. Czasami przydatne może być zezwolenie na takie odchylenia, aby pomóc pacjentom zachować równowagę emocjonalną. Jednak zbadaj dalej, czy humor wydaje się prowadzić do radykalnej zmiany tematu, który wydawał się ważny i / lub emocjonalnie istotny. Humor może również skierować klinicysta w kierunku nowych obszarów do zbadania.

Lekki żart pacjenta (np. o seksie) może być pierwszym krokiem do wprowadzenia tematu, który później nabiera znaczenia.

Ze strony klinicysty humor może mieć charakter ochronny i obronny. Tak jak pacjent może odczuwać niepokój lub dyskomfort, tak samo może czuć się osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad. Uważaj, bo humor może przynieść odwrotny skutek. Może to zostać odebrane jako kpina. Może również pozwolić zarówno pacjentowi, jak i klinicyście uniknąć ważnych tematów. Czasami humor jest wspaniałym sposobem na pokazanie ludzkich cech rozmówcy i tym samym zbudowanie terapeutycznego sojuszu. Mimo wszystko pamiętaj o problematycznych aspektach humoru, zwłaszcza gdy ty i twój pacjent nie znacie się dobrze.

19. Jak ocenia się zamiary samobójcze?

Ze względu na częstość występowania zaburzeń depresyjnych i ich związek z samobójstwem, podczas pierwszego wywiadu zawsze należy uwzględnić możliwość wystąpienia intencji samobójczych. Pytanie o samobójstwo nie sprowokuje do aktu. Jeśli temat nie pojawia się spontanicznie, można użyć kilku pytań, aby wydobyć myśli pacjenta na temat samobójstwa (wymienione w kolejności, w jakiej można je wykorzystać do rozpoczęcia dyskusji):

■Jak źle się czujesz?

■ Czy myślałeś o zrobieniu sobie krzywdy?

■ Czy chciałeś umrzeć?

■ Czy myślałeś o zabiciu się?

■ Czy próbowałeś?

-Jak, kiedy i co doprowadziło do twojej próby?

-Jeśli nie próbowałeś, co skłoniło cię do powstrzymania się?

■ Czy czujesz się bezpiecznie wracając do domu?

-Jakie ustalenia można poczynić, aby zwiększyć twoje bezpieczeństwo i zmniejszyć ryzyko działania pod wpływem myśli samobójczych?

20. Jak najlepiej zakończyć pierwszą rozmowę ewaluacyjną?

Jednym ze sposobów jest zapytanie pacjenta, czy ma jakieś konkretne pytania lub wątpliwości, na które nie odpowiedział. Po omówieniu takich zagadnień krótko podsumuj istotne wrażenia i wnioski diagnostyczne, a następnie zasugeruj sposób postępowania. Bądź tak jasny, jak to możliwe, jeśli chodzi o sformułowanie problemu, diagnozę i kolejne kroki. To czas, aby wspomnieć o konieczności wykonania jakichkolwiek badań, w tym badań laboratoryjnych i dalszych badań psychologicznych oraz uzyskania zgody na spotkanie lub rozmowę z ważnymi osobami, które mogą dostarczyć potrzebnych informacji lub powinny zostać uwzględnione w planie leczenia.

Zarówno klinicysta, jak i pacjent powinni uznać, że plan jest wstępny i może zawierać alternatywy, które wymagają dalszej dyskusji. Jeśli zalecone jest leczenie, klinicysta powinien opisać konkretne korzyści i oczekiwany przebieg, a także poinformować pacjenta o potencjalnych skutkach ubocznych, działaniach niepożądanych i alternatywnych metodach leczenia. Często pacjenci chcą przemyśleć sugestie, uzyskać więcej informacji na temat leków lub porozmawiać z członkami rodziny. W większości przypadków sytuacja kliniczna nie jest na tyle wyłaniająca się, aby podczas pierwszego wywiadu konieczne było podjęcie zdecydowanych działań. Należy jednak jasno przedstawiać zalecenia, nawet jeśli są one wstępne i ukierunkowane przede wszystkim na dalszą diagnostykę.

W tym momencie kuszące jest zapewnienie fałszywego zapewnienia, na przykład: „Wiem, że wszystko będzie dobrze". Jest całkowicie uzasadnione — a nawet lepsze — dopuszczanie niepewności, gdy niepewność istnieje. Pacjenci mogą tolerować niepewność, jeśli widzą, że klinicysta ma plan dalszego wyjaśnienia problemu i wypracowania solidnego planu leczenia.

Taka dyskusja może wymagać przedłużenia, dopóki nie będzie jasne, czy pacjent może bezpiecznie opuścić szpital lub czy wymaga przyjęcia do szpitala).

Robert Waldinger M.D.

Alan M. Jacobson M.D.

WSTĘPNY WYWIAD PSYCHIATRYCZNY (tłumaczenie Google)

Robert Waldinger

Alan M.Jacobson

1 .Jakie są główne cele pierwszego wywiadu psychiatrycznego?

Postawienie wstępnej diagnostyki różnicowej i sformułowanie planu leczenia. Cele te osiąga się poprzez:

Zbieranie informacji:

- Główne dolegliwości, problem: historia obecnych i przeszłych myśli samobójczych lub wyobrażeń o zabójstwie

- Historia przedstawianych problemów: aktualna i przeszła historia doświadczania przemocy (np. przemoc domowa, znęcanie się nad dziećmi)

- Czynniki wywołujące: historia wcześniejszych problemów ze zdrowiem psychicznym, w tym diagnoza i leczenie psychiatryczne

- Objawy: przebieg i nasilenie dolegliwości w kontekście rozwoju i doświadczeń społecznych

- Afektywny: historia doświadczeń kryzysu psychicznego w rodzinie i wśród osób z osobistej sieci społecznej

- Poznawczy: historia rozwoju poznawczego

- Fizyczny: historia doświadczenia chorób somatycznych i ich leczenia

- Używanie i nadużywanie substancji:

- Doświadczenia zmian w pełnieniu ról społecznych i funkcjonowaniu społecznym:

■ Dojście do empatycznego zrozumienia, jak czuje się pacjent. To zrozumienie jest podstawą do nawiązania relacji z pacjentem.

Kiedy klinicysta uważnie słucha, a następnie wyraża uznanie dla zmartwień i trosk pacjenta, pacjent zyskuje poczucie, że jest rozumiany. To poczucie bycia zrozumianym jest podstawą całego późniejszego leczenia i pozwala klinicyście zainicjować związekw którym można zawrzeć sojusz na rzecz leczenia.

2. To dużo, na czym należy się skupić podczas pierwszego spotkania. A pomoc pacjentowi?

Wstępna diagnoza i plan leczenia mogą być szczątkowe. Rzeczywiście, gdy pacjenci są w kryzysie, historia może być niejasna, niekompletna lub zawężona. W rezultacie niektóre interwencje są podejmowane nawet wtedy, gdy zbierane są podstawowe informacje o

historii, relacjach rodzinnych i obecnych stresorach. Bardzo ważne jest, aby pamiętać, że trudności emocjonalne często powodują izolację. Doświadczenie dzielenia się swoim problemem

z zatroskanym słuchaczem może samo w sobie przynieść ogromną ulgę. Tak więc wstępny wywiad jest początkiem leczenia jeszcze przed ustaleniem formalnego planu leczenia.

3. Jak powinna być zorganizowana rozmowa wstępna?

Nie ma jednego ideału, ale warto pomyśleć o wstępnej rozmowie zgłoszeniowej jako składającej się z trzech elementów:

Nawiąż wstępny kontakt z pacjentem i zapytaj o zgłaszaną skargę lub problemy, czyli o to, co sprowadziło pacjenta na pierwsze spotkanie. Niektórzy pacjenci opowiadają swoje historie bez większych wskazówek ze strony klinicysty, podczas gdy inni wymagają wyraźnych instrukcji w formie konkretnych pytań, które pomogą im uporządkować myśli. Podczas tej fazy pierwszego wywiadu pacjent powinien mieć jak najwięcej możliwości podążania za własnymi schematami myślowymi.

Uzyskaj określone informacje, w tym historię prezentowanych problemów, istotne informacje medyczne, pochodzenie rodzinne, historię społeczną oraz określone objawy i wzorce zachowań. Formalnie przetestuj stan psychiczny (patrz ten rozdział).

Zapytaj, czy pacjent ma jakieś pytania lub o których nie wspomniał obawy. Następnie pacjent otrzymuje wstępne zalecenia dotyczące dalszej oceny i/lub rozpoczęcia leczenia.

Chociaż te trzy części wywiadu można rozpatrywać oddzielnie, często przeplatają się one ze sobą, np. obserwacje stanu psychicznego można prowadzić od momentu spotkania klinicysty z pacjentem.

Stosowny wywiad medyczny i rodzinny może zostać przywołany w trakcie przedstawiania innych obaw, a pacjenci mogą zadawać ważne pytania dotyczące zaleceń dotyczących leczenia, gdy przedstawiają swój początkowy wywiad.

4. Czy wstępna ocena różni siew przypadku złożonych sytuacji?

Wstępna ocena psychiatryczna może wymagać więcej niż jednej sesji w złożonych sytuacjach - na przykład podczas oceny dzieci lub rodzin lub oceny przydatności pacjenta do określonego podejścia terapeutycznego, takiego jak krótka psychoterapia. Wstępna ocena może również wymagać zebrania informacji z innych źródeł: rodziców, dzieci, współmałżonka, najlepszego przyjaciela, nauczyciela, funkcjonariuszy policji i/lub innych pracowników służby zdrowia. Kontakty te mogą zostać włączone do pierwszej wizyty lub mogą wystąpić później. Pierwszym krokiem w dokonywaniu takich usta leń jest wyjaśnienie pacjentowi powodu ich zawarcia oraz uzyskanie wyraźnej, pisemnej zgody na kontakt.

5. Jak należy podejść do źródła skierowań?

Prawie zawsze właściwe jest skontaktowanie się ze źródłem skierowania w celu zebrania informacji i wyjaśnienia wstępnych wrażeń diagnostycznych i planów leczenia. Wyjątki mogą wystąpić, gdy skierowanie pochodzi od innych pacjentów, przyjaciół lub innych osób niebędących profesjonalistami, których pacjent chce wykluczyć z leczenia.

6. Czy istnieją jakieś odmiany tych wytycznych dla wstępnej oceny?

Konkretne orientacje teoretyczne mogą dyktować istotne różnice w wstępnej ocenie. Na przykład terapeuta behawioralny kieruje dyskusję do konkretnych analiz bieżących problemów i poświęca niewiele czasu na doświadczenia z wczesnego dzieciństwa. Ocena psychofarmakologiczna kładzie nacisk na specyficzne wzorce objawów, reakcje na wcześniejsze leczenie farmakologiczne oraz występowanie chorób psychicznych w rodzinie. Podejście przedstawione w tym rozdziale jest zestawem zasad o szerokim zastosowaniu, które można zastosować w ocenie większości pacjentów.

7. W jaki sposób zbierane są informacje z wywiadu?

Klinicysta musi dowiedzieć się jak najwięcej o tym, jak pacjent myśli i czuje. Podczas wywiadu klinicznego zbierane są informacje z tego, co pacjent mówi klinicyście; krytycznie ważne wskazówki pochodzą również z tego, jak rozwija się historia. Zatem zarówno treść wywiadu (tj. to, co mówi pacjent), jak i przebieg wywiadu (tj. sposób, w jaki pacjent to mówi) oferują ważne drogi do zrozumienia problemów pacjenta. Weź pod uwagę kolejność przekazywanych informacji, komfort mówienia o nich, emocje związane z dyskusją, reakcje pacjenta na pytania i wstępne uwagi, spójność prezentacji oraz czas podania informacji. Pełne opracowanie takich informacji może zająć jedną lub kilka sesji w ciągu dni, tygodni lub miesięcy, ale podczas pierwszego wywiadu można zasugerować głębsze obawy.

Na przykład 35-letnia kobieta zgłosiła zaniepokojenie nawracającą astmą jej syna i związanymi z tym trudnościami w szkole. Swobodnie mówiła o swoich obawach i zasięgała rady, jak pomóc synowi. Zapytana o myśli męża, na chwilę się uspokoiła. Następnie powiedziała, że podziela jej obawy i przeniosła dyskusję z powrotem na jej syna. Jej wahanie wskazywało na inne problemy, które pozostały nierozwiązane podczas pierwszej sesji. Rzeczywiście, zaczęła kolejną sesję od pytania: „Czy mogę mówić o czymś innym niż o moim synu?". Uspokoiwszy się, opisała chroniczną złość męża na syna z powodu jego „słabości". Jego złość i jej własne uczucia w odpowiedzi stały się ważnym celem późniejszego leczenia.

8. Jak należy rozpocząć rozmowę zgłoszeniową?

Tu i teraz jest miejscem, w którym zaczyna się wszystkie wywiady. Można zadać jedno z wielu prostych pytań: „Co cię dzisiaj do mnie sprowadza? Możesz mi powiedzieć, co cię trapi?Jak

Czy to dlatego, że zdecydowałeś się umówić na to spotkanie? W przypadku niespokojnych pacjentów przydatna jest struktura: wczesne zapytanie o wiek, stan cywilny i sytuację życiową może dać im czas na stanie się czują się komfortowo, zanim przystąpią do opisu swoich problemów. Jeśli lęk jest ewidentny, prosty komentarz na temat lęku może pomóc pacjentom porozmawiać o swoich zmartwieniach.

9. Czy wysoce ustrukturyzowany format jest ważny?

Nie. Pacjenci muszą mieć możliwość uporządkowania swoich informacji w sposób, który im najbardziej odpowiada. Klinicysta, który przedwcześnie poddaje pacjenta strumieniowi konkretnych pytań, ogranicza informacje o własnym procesie myślowym pacjenta, nie uczy się, jak pacjent radzi sobie z ciszą lub smutkiem, odcina mu możliwość podpowiedzi lub wprowadzenia nowych tematów.

Ponadto zadanie polegające na formułowaniu jednego konkretnego pytania po drugim może zakłócać zdolność lekarza do słuchania i rozumienia pacjenta.

Nie oznacza to, że należy unikać konkretnych pytań. Często pacjenci udzielają rozbudowanych odpowiedzi na konkretne pytania, takie jak „Kiedy byłeś żonaty?" Ich odpowiedzi mogą otworzyć nowe możliwości dochodzenia. Kluczem jest unikanie szybkiego podejścia i umożliwienie pacjentom rozwinięcia myśli.

10. Jak należy zadawać pytania?

Pytania powinny być formułowane w sposób zachęcający pacjentów do rozmowy. Pytania otwarte, które nie wskazują odpowiedzi, zwykle pozwalają ludziom rozwinąć więcej niż pytania szczegółowe lub naprowadzające. Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, pytania naprowadzające (np. „Czy czułeś się smutny, kiedy twoja dziewczyna się wyprowadziła?") mogą przeszkadzać w rozmowie, ponieważ mogą sprawiać wrażenie, że osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad oczekuje od pacjenta pewnych uczuć. Niewiodące pytania („Jak się czułeś, kiedy twoja dziewczyna się wyprowadziła?") są równie bezpośrednie i skuteczniejsze.

11. Jaki jest skuteczny sposób radzenia sobie z wahaniami pacjentów?

Kiedy pacjenci potrzebują pomocy w opracowaniu, proste stwierdzenie i/lub prośba mogą wywołać więcej informacji: „Opowiedz mi o tym więcej". Powtarzanie lub zastanawianie się nad tym, co mówią pacjenci, również zachęca ich do otwarcia się (np. „Mówiłeś o swojej dziewczynie"). Czasami komentarze, które konkretnie odzwierciedlają zrozumienie przez lekarza odczuć pacjenta w związku ze zdarzeniami, mogą pomóc pacjentowi rozwinąć temat. Takie podejście zapewnia potwierdzenie zarówno klinicyście, jak i pacjentowi, że nadają na tych samych falach. Gdy klinicysta prawidłowo zareaguje na ich odczucia, pacjenci często potwierdzają odpowiedź poprzez dalszą dyskusję. Pacjent, którego dziewczyna odeszła, może czuć się zrozumiany i swobodniej rozmawiać o stracie po komentarzu typu „Wydajesz się zniechęcony wyprowadzką swojej dziewczyny".

12. Podaj przykład, jak kompleksowe gromadzenie informacji może wskazać problem.

Starszy mężczyzna został skierowany z powodu narastającego przygnębienia. W pierwszym wywiadzie opisał najpierw trudności finansowe, a następnie poruszył niedawny rozwój problemów medycznych, których kulminacją była diagnoza raka prostaty. Kiedy zaczął mówić o raku i chęci poddania się, zamilkł. W tym momencie wywiadu klinicysta wyraził uznanie, że pacjent wydawał się być przytłoczony narastającymi problemami finansowymi i, w większości, wszystko, medyczne zmiany. Pacjent cicho skinął głową, a następnie rozwinął swoje szczególne obawy dotyczące tego, jak jego żona będzie sobie radzić po jego śmierci. Nie czuł, że jego dzieci będą jej pomocne. Nie było jeszcze jasne, czyjego pesymizm odzwierciedlał depresyjną nadmierną reakcję na diagnozę raka, czy też dokładną ocenę rokowania. Dalsza ocena objawów i stanu psychicznego oraz krótka rozmowa z żoną w dalszej części spotkania wykazały, że rokowania są całkiem dobre. Następnie leczenie koncentrowało się na jego depresyjnych reakcjach na diagnozę.

13. Jak najlepiej formułować pytania?

Klinicysta powinien używać języka, który nie jest techniczny ani nadmiernie intelektualny. Jeśli to możliwe, należy używać własnych słów pacjenta. Jest to szczególnie ważne w przypadku spraw intymnych, takich jak problemy seksualne. Ludzie opisują swoje doświadczenia seksualne w dość zróżnicowanym języku. Jeśli pacjent mówi, że jest gejem, użyj dokładnie tego terminu, a nie pozornie równoważnego terminu, takiego jak homoseksualista. Ludzie używają niektórych słów, a innych nie, ze względu na specyficzne konotacje, jakie niosą dla nich różne słowa; na początku takie rozróżnienia mogą nie być oczywiste dla klinicysty.

14. A co z pacjentami, którzy nie są wstanie porozumiewać się w spójny sposób?

Klinicysta musi przez cały czas być świadomy tego, co dzieje się podczas wywiadu. Jeśli pacjent ma halucynacje lub jest bardzo zdenerwowany, nieuznanie zdenerwowania lub niepokojącego doświadczenia może zwiększyć niepokój pacjenta.

Omówienie aktualnego zdenerwowania pacjenta pomaga złagodzić napięcie i mówi pacjentowi, że lekarz słucha. Jeśli historia pacjenta jest chaotyczna lub niejasna, uznaj trudności w zrozumieniu pacjenta i oceń możliwe przyczyny (np. psychoza z poluzowanymi skojarzeniami vs. lęk przed wizytą).

Kiedy pytania ogólne (np. „Opowiedz mi coś o swoim pochodzeniu") są nieskuteczne, może być konieczne zadawanie szczegółowych pytań dotyczących rodziców, szkoły i dat wydarzeń. Pamiętaj jednak, że zadawanie niekończących się pytań w celu złagodzenia własnego niepokoju, a nie pacjenta, może być kuszące.

15. Podsumuj kluczowe punkty, o których należy pamiętać podczas pierwszego wywiadu.

Umożliwienie pacjentowi swobodnego opowiedzenia własnej historii musi być zrównoważone poprzez uwzględnienie zdolności pacjenta do skupienia się na istotnych tematach. Niektóre osoby wymagają wskazówek od klinicysty, aby uniknąć zagubienia się w stycznych tematach. Inni mogą potrzebować spójnej struktury, ponieważ mają problemy z uporządkowaniem myśli, być może z powodu wysokiego stopnia niepokoju. Empatyczny komentarz na temat niepokoju pacjenta może go zmniejszyć, a tym samym doprowadzić do wyraźniejszej komunikacji.

Niektóre wytyczne dotyczące rozmowy zgłoszeniowej

• Pozwól, aby pierwsza część wstępnego wywiadu podążała za tokiem myślenia pacjenta.

• Zapewnij strukturę, aby pomóc pacjentom, którzy mają problemy z uporządkowaniem myśli lub dokończeniem uzyskiwania określonych danych.

• Formułuj pytania, aby zachęcić pacjenta do rozmowy (np. pytania otwarte, nienaprowadzające).

• Używaj słów pacjenta.

• Bądź wyczulony na wczesne oznaki utraty kontroli nad zachowaniem (np. wstawanie do tempa).

• Zidentyfikuj mocne strony pacjenta oraz obszary problemowe.

• Unikaj żargonu i technicznego języka.

• Unikaj pytań zaczynających się od „dlaczego".

• Unikaj przedwczesnych zapewnień.

• Nie pozwalaj pacjentom zachowywać się niewłaściwie (np. łamać lub rzucać przedmiotami).

• postaw granice wobec wszelkich zagrażających zachowań i w razie potrzeby wezwij niezbędną pomoc.

16. Jakich konkretnych pułapek należy unikać podczas wstępna rozmowa zgłoszeniowa?

Unikaj żargonu lub terminów technicznych, chyba że jest to jasno wyjaśnione i konieczne. Pacjenci mogą używać żargonu, na przykład: „Miałem paranoję". Jeśli pacjent używa słowa technicznego, zapytaj o jego znaczenie. Możesz być zaskoczony zrozumieniem pacjenta. Na przykład pacjenci mogą używać słowa „paranoik", aby zasugerować strach przed dezaprobatą społeczną lub pesymizm co do przyszłości. Uważaj również, aby podczas wywiadu przypisać problemom pacjenta etykietę diagnostyczną. Pacjent może być przestraszony i zdezorientowany etykietą.

Ogólnie rzecz biorąc, unikaj zadawania pytań zaczynających się od „dlaczego". Pacjenci mogą nie wiedzieć, dlaczego mają określone doświadczenia lub uczucia i mogą czuć się nieswojo, a nawet głupio, jeśli uważają, że ich odpowiedzi nie są „dobre". Pytanie dlaczego oznacza również, że oczekujesz od pacjenta szybkich wyjaśnień.

Pacjenci dowiadują się więcej o źródłach swoich problemów, zastanawiając się nad swoim życiem podczas wywiadu i kolejnych sesji. Kiedy masz ochotę zapytać dlaczego, sformułuj pytanie tak, aby wywołało bardziej szczegółową odpowiedź.

Alternatywy obejmują „Co się stało?" „Jak to się stało?" lub „Co o tym myślisz?'

Unikaj przedwczesnej pewności siebie. Kiedy pacjenci są zdenerwowani, jak to często bywa podczas pierwszych wywiadów, osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad może ulec pokusie, by rozwiać obawy pacjenta, mówiąc: „Wszystko będzie dobrze" lub „Nie ma tu nic naprawdę złego".

Jednak zapewnienie jest prawdziwe tylko wtedy, gdy klinicysta (1) dokładnie zbadał charakter i zakres problemów pacjenta oraz (2) jest pewien tego, co mówi pacjentowi. Przedwczesne zapewnienie może zwiększyć niepokój pacjenta, sprawiając wrażenie, że lekarz wyciągnął pochopne wnioski bez dokładnej oceny lub po prostu mówi to, co pacjent chce usłyszeć. Pozostawia również pacjentów samych ze swoimi obawami oto, co naprawdę jest nie tak.

Co więcej, przedwczesne zapewnienia raczej zamykają dyskusję niż zachęcają do dalszych badań problem. Bardziej uspokajające może być zapytanie pacjenta, co go niepokoi. Proces (tj. charakter interakcji) pociesza pacjenta bardziej niż jakakolwiek pojedyncza rzecz, którą może powiedzieć klinicysta.

Postaw granice zachowaniom.

Z powodu problemów psychiatrycznych niektórzy pacjenci mogą stracić kontrolę nad sesją. Chociaż opisane tutaj podejście kładzie nacisk na pozwolenie pacjentowi na kierowanie dużą częścią werbalnej dyskusji, czasami należy wyznaczyć granice niewłaściwego zachowania. Pacjenci, którzy są podnieceni i chcą się rozebrać lub grożą, że rzucą przedmiotem, muszą być kontrolowani.

Cel ten najczęściej osiąga się poprzez komentowanie narastającego pobudzenia, omawianie go, dopytywanie o źródła niepokoju i informowanie pacjentów o granicach akceptowalnego zachowania. W rzadkich przypadkach pomoc z zewnątrz może być konieczna (np. ochroniarze na oddziale ratunkowym), zwłaszcza jeśli zachowanie się nasila, a przesłuchujący wyczuwa niebezpieczeństwo. Wywiad należy przerwać do czasu, gdy zachowanie pacjenta będzie można opanować w taki sposób, aby można było bezpiecznie kontynuować.

17. O czym często zapomina się w ocenie pacjentów?

Nowy pacjent nawiązuje kontakt z klinicystą z powodu problemów i zmartwień; to są uzasadnione pierwsze tematy wywiadu. Pomocne jest również zrozumienie mocnych stron pacjenta, które są podstawą, na której będzie opierać się leczenie. Mocne strony obejmują sposoby, w jakie pacjent z powodzeniem radził sobie z przeszłym i obecnym cierpieniem, osiągnięciami, źródłami wewnętrznej wartości, przyjaźniami, osiągnięciami w pracy i wsparciem rodziny. Mocne strony obejmują również hobby i zainteresowania, które pacjenci wykorzystują do walki ze swoimi zmartwieniami.

Pytania typu „Z czego jesteś dumny?" lub „Co lubisz w sobie?" może ujawnić takie informacje.

Często informacje wychodzą po namyśle w trakcie rozmowy. Na przykład jeden pacjent był bardzo dumny ze swojej wolontariatu w kościele. Wspomniał o tym tylko mimochodem, omawiając swoje zajęcia na tydzień przed spotkaniem. Jednak ta praca wolontariacka była jego jedynym aktualnym źródłem osobistej wartości. Zwrócił się do niego, gdy zdenerwował się brakiem sukcesów w karierze.

18. Jaka jest rola humoru w wywiadzie?

Pacjenci mogą używać humoru, aby odwrócić rozmowę od tematów wywołujących lęk lub niepokojących. Czasami przydatne może być zezwolenie na takie odchylenia, aby pomóc pacjentom zachować równowagę emocjonalną. Jednak zbadaj dalej, czy humor wydaje się prowadzić do radykalnej zmiany tematu, który wydawał się ważny i / lub emocjonalnie istotny. Humor może również skierować klinicysta w kierunku nowych obszarów do zbadania.

Lekki żart pacjenta (np. o seksie) może być pierwszym krokiem do wprowadzenia tematu, który później nabiera znaczenia.

Ze strony klinicysty humor może mieć charakter ochronny i obronny. Tak jak pacjent może odczuwać niepokój lub dyskomfort, tak samo może czuć się osoba przeprowadzająca wywiad. Uważaj, bo humor może przynieść odwrotny skutek. Może to zostać odebrane jako kpina. Może również pozwolić zarówno pacjentowi, jak i klinicyście uniknąć ważnych tematów. Czasami humor jest wspaniałym sposobem na pokazanie ludzkich cech rozmówcy i tym samym zbudowanie terapeutycznego sojuszu. Mimo wszystko pamiętaj o problematycznych aspektach humoru, zwłaszcza gdy ty i twój pacjent nie znacie się dobrze.

19. Jak ocenia się zamiary samobójcze?

Ze względu na częstość występowania zaburzeń depresyjnych i ich związek z samobójstwem, podczas pierwszego wywiadu zawsze należy uwzględnić możliwość wystąpienia intencji samobójczych. Pytanie o samobójstwo nie sprowokuje do aktu. Jeśli temat nie pojawia się spontanicznie, można użyć kilku pytań, aby wydobyć myśli pacjenta na temat samobójstwa (wymienione w kolejności, w jakiej można je wykorzystać do rozpoczęcia dyskusji):

■Jak źle się czujesz?

■ Czy myślałeś o zrobieniu sobie krzywdy?

■ Czy chciałeś umrzeć?

■ Czy myślałeś o zabiciu się?

■ Czy próbowałeś?

-Jak, kiedy i co doprowadziło do twojej próby?

-Jeśli nie próbowałeś, co skłoniło cię do powstrzymania się?

■ Czy czujesz się bezpiecznie wracając do domu?

-Jakie ustalenia można poczynić, aby zwiększyć twoje bezpieczeństwo i zmniejszyć ryzyko działania pod wpływem myśli samobójczych?

20. Jak najlepiej zakończyć pierwszą rozmowę ewaluacyjną?

Jednym ze sposobów jest zapytanie pacjenta, czy ma jakieś konkretne pytania lub wątpliwości, na które nie odpowiedział. Po omówieniu takich zagadnień krótko podsumuj istotne wrażenia i wnioski diagnostyczne, a następnie zasugeruj sposób postępowania. Bądź tak jasny, jak to możliwe, jeśli chodzi o sformułowanie problemu, diagnozę i kolejne kroki. To czas, aby wspomnieć o konieczności wykonania jakichkolwiek badań, w tym badań laboratoryjnych i dalszych badań psychologicznych oraz uzyskania zgody na spotkanie lub rozmowę z ważnymi osobami, które mogą dostarczyć potrzebnych informacji lub powinny zostać uwzględnione w planie leczenia.

Zarówno klinicysta, jak i pacjent powinni uznać, że plan jest wstępny i może zawierać alternatywy, które wymagają dalszej dyskusji. Jeśli zalecone jest leczenie, klinicysta powinien opisać konkretne korzyści i oczekiwany przebieg, a także poinformować pacjenta o potencjalnych skutkach ubocznych, działaniach niepożądanych i alternatywnych metodach leczenia. Często pacjenci chcą przemyśleć sugestie, uzyskać więcej informacji na temat leków lub porozmawiać z członkami rodziny. W większości przypadków sytuacja kliniczna nie jest na tyle wyłaniająca się, aby podczas pierwszego wywiadu konieczne było podjęcie zdecydowanych działań. Należy jednak jasno przedstawiać zalecenia, nawet jeśli są one wstępne i ukierunkowane przede wszystkim na dalszą diagnostykę.

W tym momencie kuszące jest zapewnienie fałszywego zapewnienia, na przykład: „Wiem, że wszystko będzie dobrze". Jest całkowicie uzasadnione — a nawet lepsze — dopuszczanie niepewności, gdy niepewność istnieje. Pacjenci mogą tolerować niepewność, jeśli widzą, że klinicysta ma plan dalszego wyjaśnienia problemu i wypracowania solidnego planu leczenia.

Taka dyskusja może wymagać przedłużenia, dopóki nie będzie jasne, czy pacjent może bezpiecznie opuścić szpital lub czy wymaga przyjęcia do szpitala).

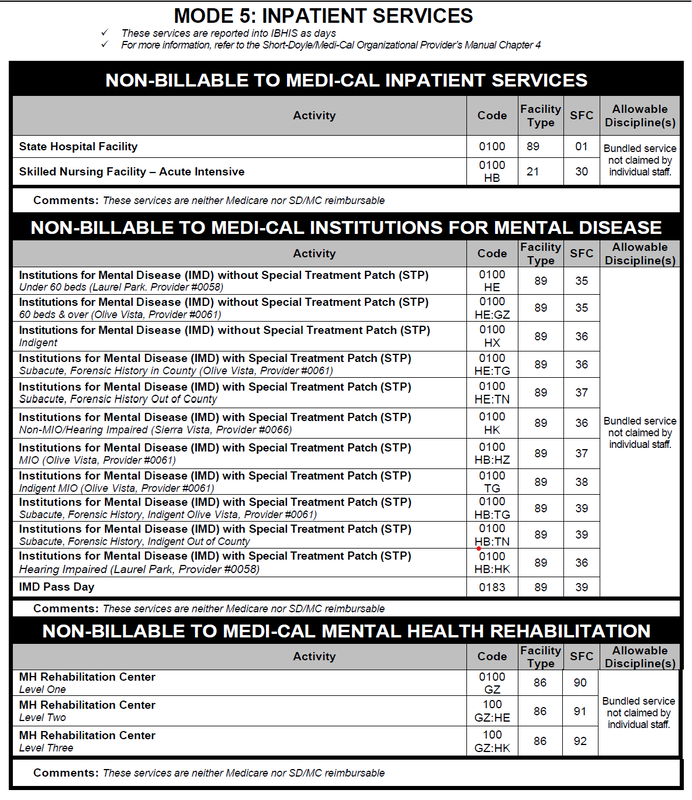

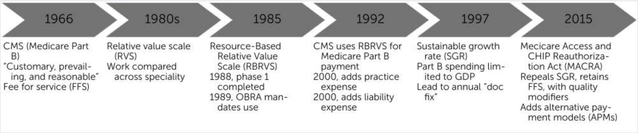

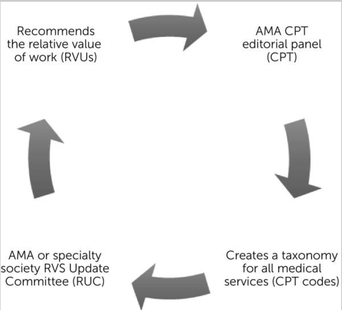

Rozliczanie świadczeń zdrowotnych w USA według wykonań „fee-for-service” (odpowiednio w Polsce - produkty rozliczeniowe w NFZ, zdarzenia medyczne w systemie IT)

BILLING and LEGAL STUFF

Your Signature (and a supervisor signature, if required)

Date of Service

Start and Stop Times of the Group

Total Time

ICD-10 Code

CPT Code

https://therathink.com/mental-health-cpt-codes/

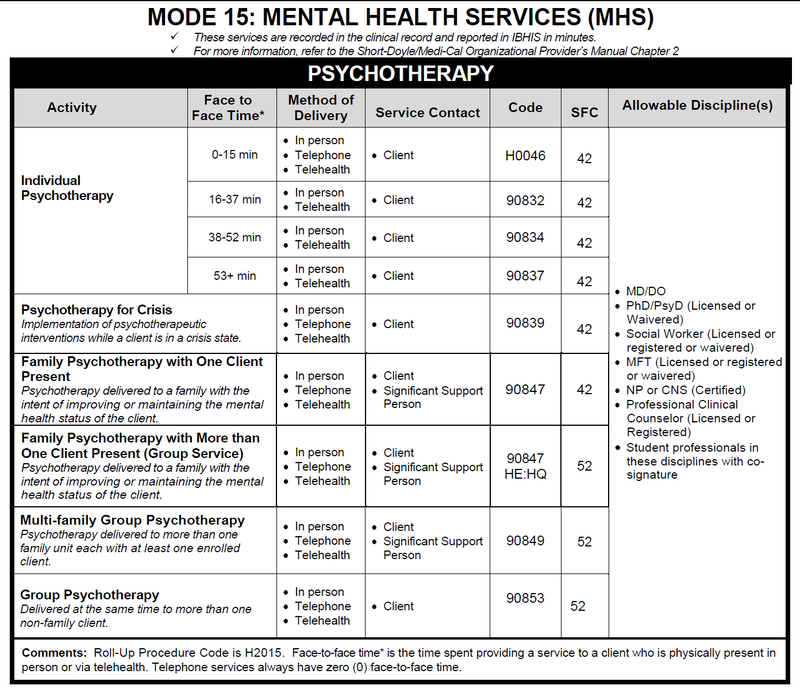

The Most Common Mental Health CPT Codes (najbardziej powszechne kody procedur w opiece psychiatrycznej)

The most common CPT Codes used by therapists and behavioral health professionals:

Outpatient Mental Health Therapist Diagnostics, Evaluation, Intake CPT Code:

Outpatient Psychiatry Diagnostics / Evaluation / Client Intake CPT Code:

● Psychotherapy must be at least 16 minutes.

● Time is very important and should be rounded to the nearest CPT Code.

● Outpatient vs. Inpatient is not important.

● E/M codes can only be used by prescribers (MD, DO, APN, PA).

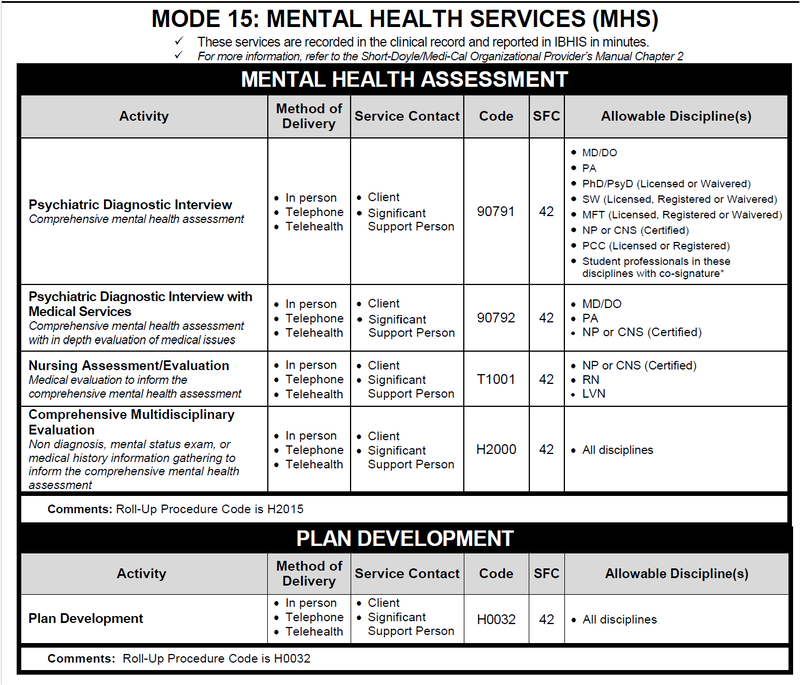

Lektura amerykańskiej klasyfikacji świadczeń w opiece psychiatrycznej opracowanej do rozliczeń „fee-for-service” pozwala dokonać porównań i wyciągnąć różne wnioski. W rozliczeniach za wykonanie świadczeń bierze się pod uwagę:

Personel – kto wykonywał świadczenie

Termin – data wykonania świadczenia

Czas rozpoczęcia i zakończenia, czas trwania świadczenia

ICD-10 rozpoznanie

KOD ŚWIADCZENIA/PROCEDURY

Lista KODÓW jest tak rozbudowana, że zawiera w sobie sumę informacji: profesjonalista, rodzaj świadczenia i czas jego wykonania.

Ciekawostką jest to, że “diagnostyczny wywiad psychiatryczny” 90791 – Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation (usually just one/client is covered) dzieli się na wywiad, który wykonują wszyscy pracownicy działalności podstawowej, oraz wywiad ze świadczeniem medycznym – porada lekarska diagnostyczna. W Polsce, z niezrozumiałych powodów porady diagnostyczne wykonuje albo lekarz psychiatra albo psycholog, co sugeruje urzędnikom nie wprost, że psychoterapeuta, pielęgniarka, terapeuta środowiskowy nie uczestniczą w procesie diagnostycznym, inaczej nie mogą spotkać się z pacjentem i porozmawiać z jakim problemem przychodzi, jak się czuje, czego potrzebuje i oczekuje!!!

Activity: Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview (Comprehensive mental health assessment) –

Allowable Discipline(s):

•Medical Doctor / Doctor of Osteopathy (completed a psychiatry residency program) lekarz psychiatra

•Physician Assistant (PA)

•Clinical Psychologist PhD/PsyD (Licensed or Waivered) psycholog

• Social Worker SW (Licensed, Registered or Waivered) pracownik socjalny

•Marriage & Family Therapist MFT (Licensed, Registered or Waivered)

•Nurse Practitioner (NP) or Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) (Certified) pielęgniarka

•Professional Clinical Counselor PCC (Licensed or Registered)

•Student professionals in these disciplines with co-signature*

Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview with Medical Services (Comprehensive mental health assessment with in depth evaluation of medical issues)

Allowable Discipline(s):

• MD/DO lekarz

• PA lekarz

• NP or CNS (Certified) pielęgniarka

BILLING and LEGAL STUFF

Your Signature (and a supervisor signature, if required)

Date of Service

Start and Stop Times of the Group

Total Time

ICD-10 Code

CPT Code

https://therathink.com/mental-health-cpt-codes/

The Most Common Mental Health CPT Codes (najbardziej powszechne kody procedur w opiece psychiatrycznej)

The most common CPT Codes used by therapists and behavioral health professionals:

Outpatient Mental Health Therapist Diagnostics, Evaluation, Intake CPT Code:

- 90791 – Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation (usually just one/client is covered)

- 90832 – Psychotherapy, 30 minutes (16-37 minutes).

- 90834 – Psychotherapy, 45 minutes (38-52 minutes).

- 90837 – Psychotherapy, 60 minutes (53 minutes and over).

- 90846 – Family or couples psychotherapy, without patient present.

- 90847 – Family or couples psychotherapy, with patient present.

- 90853 – Group Psychotherapy (not family).

- 98968 – Telephone therapy (non-psychiatrist) – limit 3 units/hours per application.

- 90839 – Psychotherapy for crisis, 60 minutes (30-74 minutes).

- +90840 – Add-on code for an additional 30 minutes (75 minutes and over). Used in conjunction with 90839.

- +90785 – Interactive Complexity add-on code. Covered below.

- 90404 – Cigna / MHN EAP CPT Code. These two companies use a unique CPT code for EAP sessions.

- 96101 – Psychological testing, interpretation and reporting by a psychologist (per Hour)

- 90880 – Hypnotherapy – limit 10 units/hours per application

- 90876 – Biofeedback

- 90849 – Multiple family group psychotherapy

- 90845 – Psychoanalysis

- Add-On CPT Code 90785 – Interactive complexity. Example: play therapy using dolls or other toys. This is an interactive complexity add-on code that is not a payable expense. This code only indicates that the treatment is complex in nature.

- Add-On CPT Code 90863 – Pharmacologic Management after therapy.

- Add-On CPT Code 99050 – Services provided in the office at times other than regularly scheduled office hours, or days when the office is normally closed.

- Add-On CPT Code 99051 – Services provided in the office during regularly scheduled evening, weekend, or holiday office hours.

- Add-On CPT Code 99354 – Additional time after the additional time of 74 minutes. Adding another 30 minutes. (Only use if the duration of your session is at least 90 minutes for 90837 or 80 minutes for 90847).

- Add-On CPT Code 99355 – Additional time after first 60 minutes. First additional 30 to 74 minutes.

- Add-On CPT Code 90840 – 30 additional minutes of psychotherapy for crisis. Used only in conjunction with CPT 90839.

- Add-On CPT Code 90833 – 30 minute psychotherapy add-on. Example: Psychiatrist evaluates medication response, then has 30 minute session.

- Add-On CPT Code 90836 – 45 minute psychotherapy add-on. Example: Clinical Nurse Specialist evaluates medication response, then has 45 minute session.

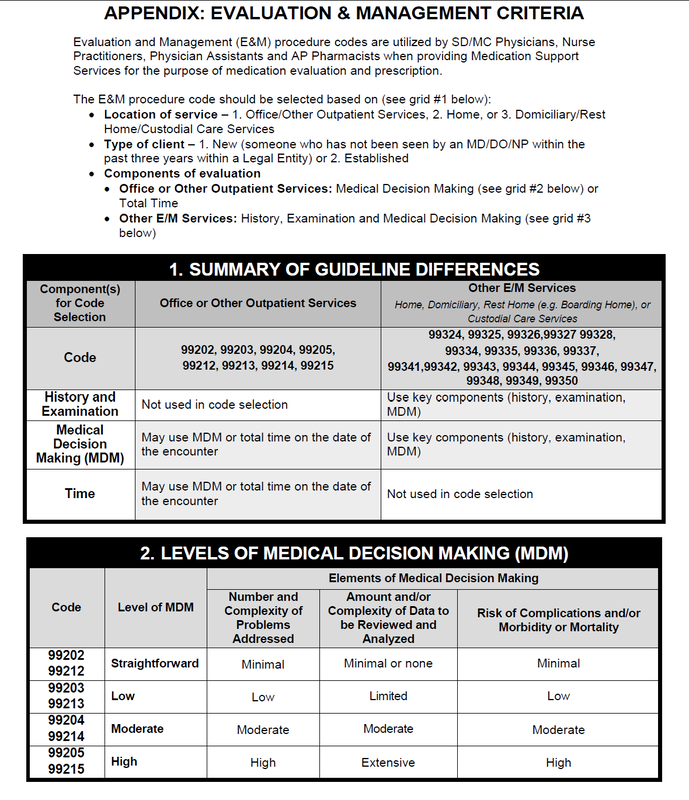

Outpatient Psychiatry Diagnostics / Evaluation / Client Intake CPT Code:

- 90792 – Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation with medical services (usually just one/client is covered)

- 99201 – E/M – New Patient Office Visit – 10 Minutes

- 99202 – E/M – New Patient Office Visit – 20 Minutes

- 99203 – E/M – New Patient Office Visit – 30 Minutes

- 99204 – E/M – New Patient Office Visit – 45 Minutes

- 99205 – E/M – New Patient Office Visit – 60 Minutes

- 99211 – E/M – Established Patients – 5 Minutes

- 99212 – E/M – Established Patients – 10 Minutes

- 99213 – E/M – Established Patients – 15 Minutes

- 99214 – E/M – Established Patients – 25 Minutes

- 99215 – E/M – Established Patients – 40 Minutes

- 99443 – Telephone therapy (psychiatrist), – limit 3 units/hours per application

● Psychotherapy must be at least 16 minutes.

● Time is very important and should be rounded to the nearest CPT Code.

● Outpatient vs. Inpatient is not important.

● E/M codes can only be used by prescribers (MD, DO, APN, PA).

Lektura amerykańskiej klasyfikacji świadczeń w opiece psychiatrycznej opracowanej do rozliczeń „fee-for-service” pozwala dokonać porównań i wyciągnąć różne wnioski. W rozliczeniach za wykonanie świadczeń bierze się pod uwagę:

Personel – kto wykonywał świadczenie

Termin – data wykonania świadczenia

Czas rozpoczęcia i zakończenia, czas trwania świadczenia

ICD-10 rozpoznanie

KOD ŚWIADCZENIA/PROCEDURY

Lista KODÓW jest tak rozbudowana, że zawiera w sobie sumę informacji: profesjonalista, rodzaj świadczenia i czas jego wykonania.

Ciekawostką jest to, że “diagnostyczny wywiad psychiatryczny” 90791 – Psychiatric Diagnostic Evaluation (usually just one/client is covered) dzieli się na wywiad, który wykonują wszyscy pracownicy działalności podstawowej, oraz wywiad ze świadczeniem medycznym – porada lekarska diagnostyczna. W Polsce, z niezrozumiałych powodów porady diagnostyczne wykonuje albo lekarz psychiatra albo psycholog, co sugeruje urzędnikom nie wprost, że psychoterapeuta, pielęgniarka, terapeuta środowiskowy nie uczestniczą w procesie diagnostycznym, inaczej nie mogą spotkać się z pacjentem i porozmawiać z jakim problemem przychodzi, jak się czuje, czego potrzebuje i oczekuje!!!

Activity: Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview (Comprehensive mental health assessment) –

Allowable Discipline(s):

•Medical Doctor / Doctor of Osteopathy (completed a psychiatry residency program) lekarz psychiatra

•Physician Assistant (PA)

•Clinical Psychologist PhD/PsyD (Licensed or Waivered) psycholog

• Social Worker SW (Licensed, Registered or Waivered) pracownik socjalny

•Marriage & Family Therapist MFT (Licensed, Registered or Waivered)

•Nurse Practitioner (NP) or Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) (Certified) pielęgniarka

•Professional Clinical Counselor PCC (Licensed or Registered)

•Student professionals in these disciplines with co-signature*

Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview with Medical Services (Comprehensive mental health assessment with in depth evaluation of medical issues)

Allowable Discipline(s):

• MD/DO lekarz

• PA lekarz

• NP or CNS (Certified) pielęgniarka

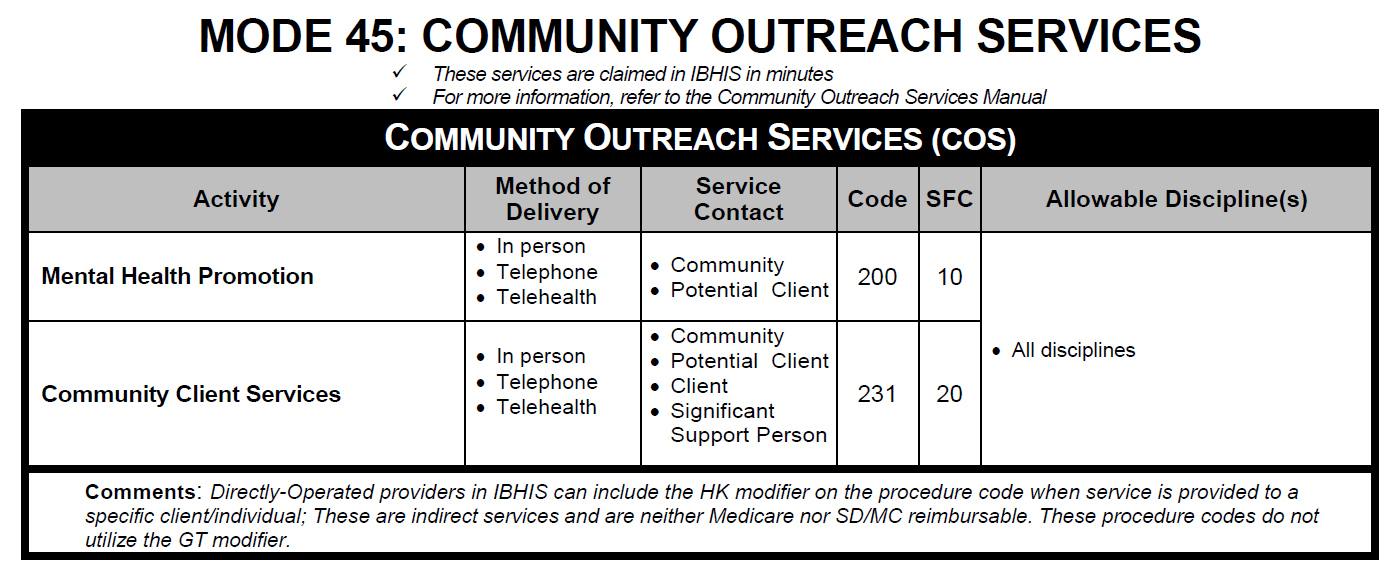

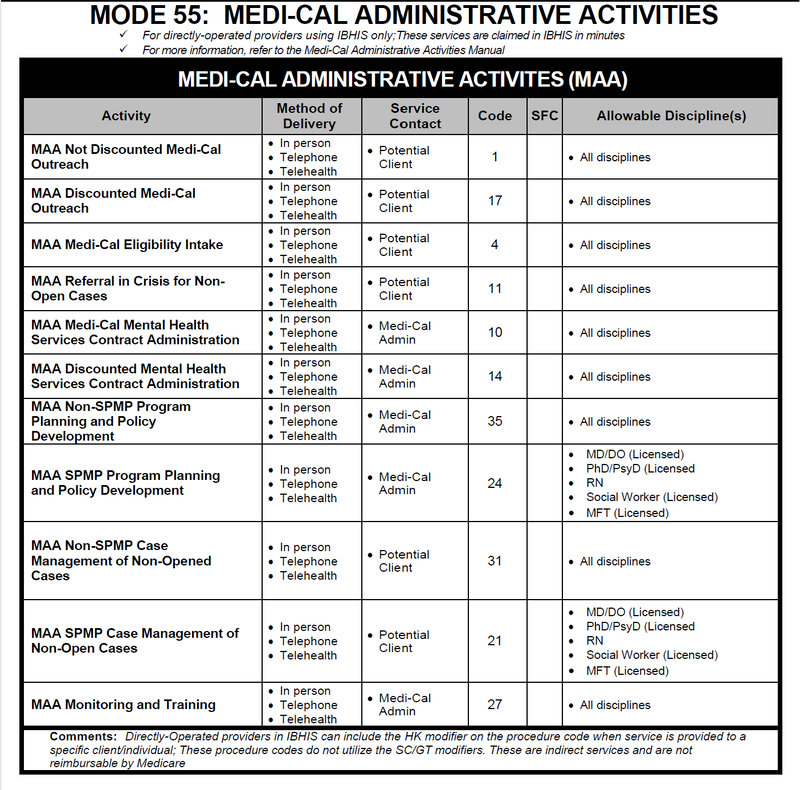

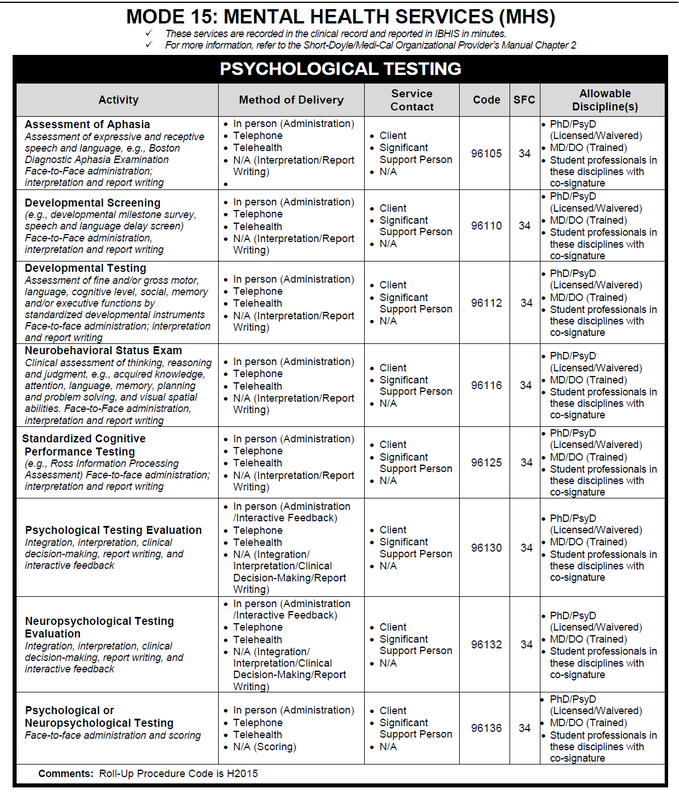

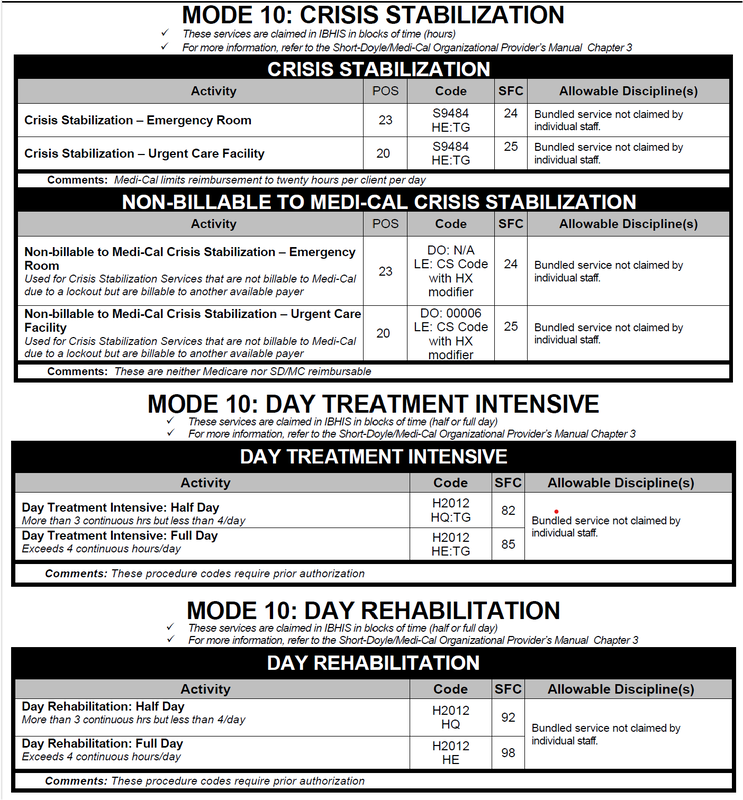

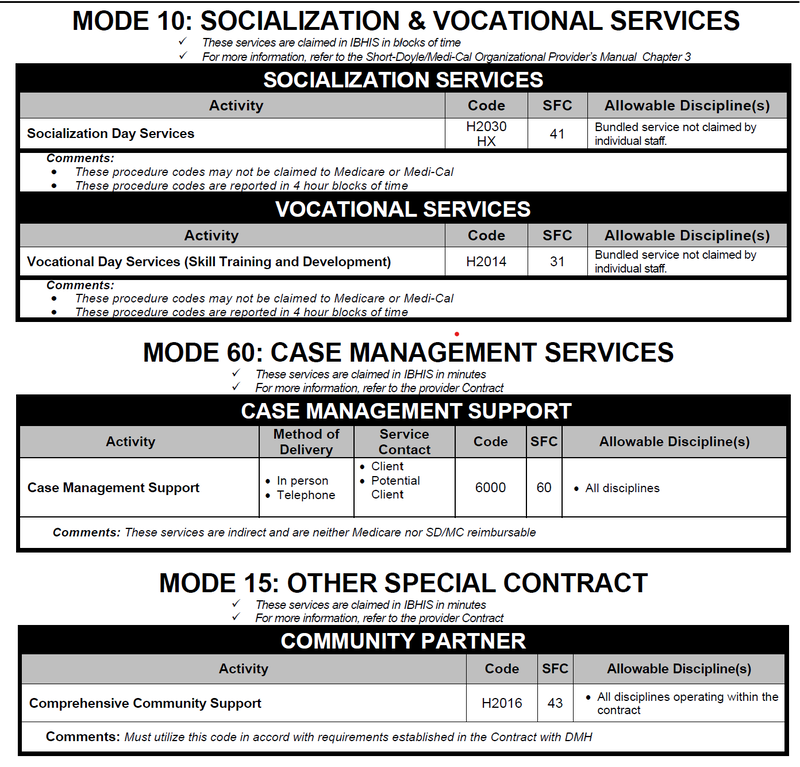

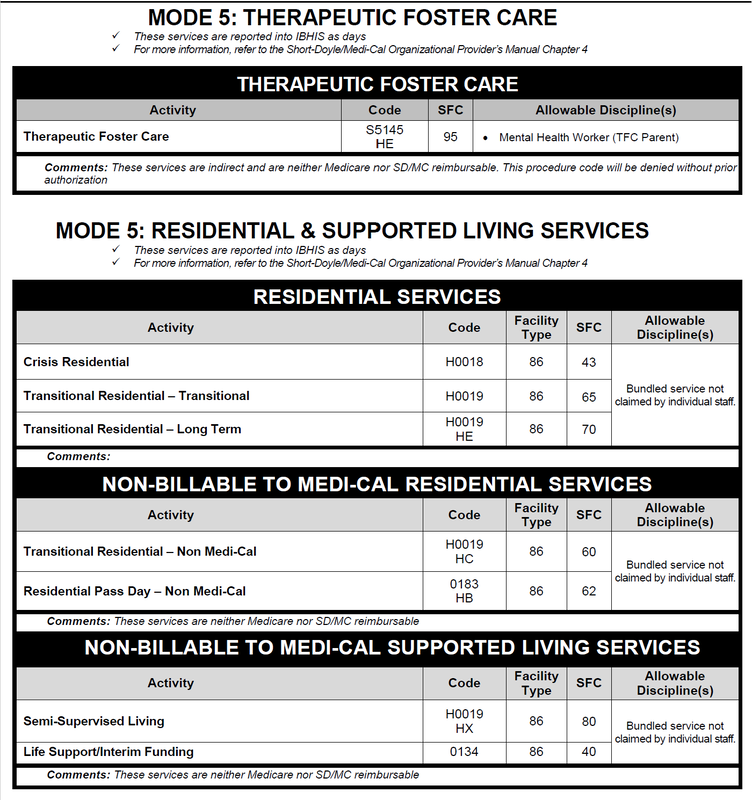

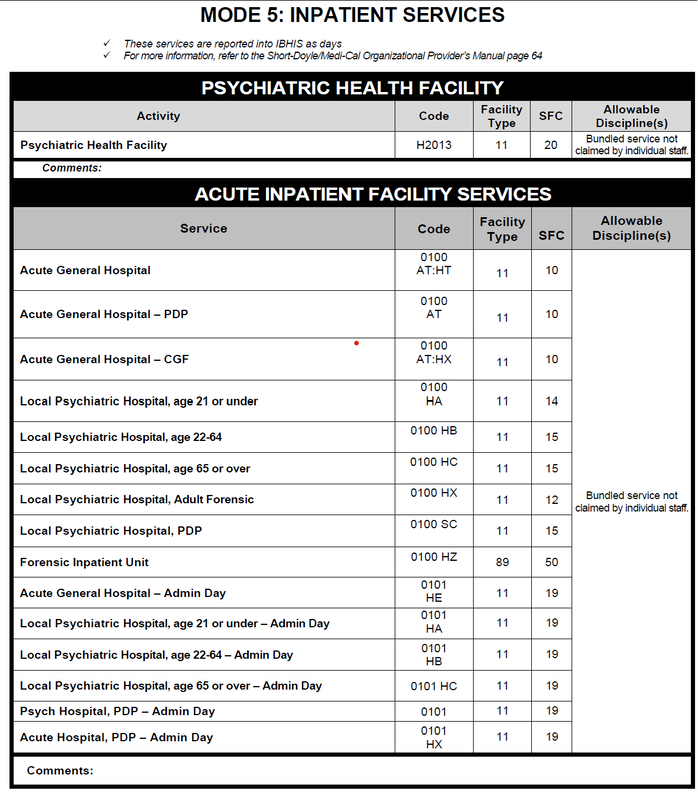

A GUIDE TO PROCEDURE CODES FOR CLAIMING MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

County of Los Angeles – Department of Mental Health Quality Assurance Division, 2017

TABLE OF CONTENTS

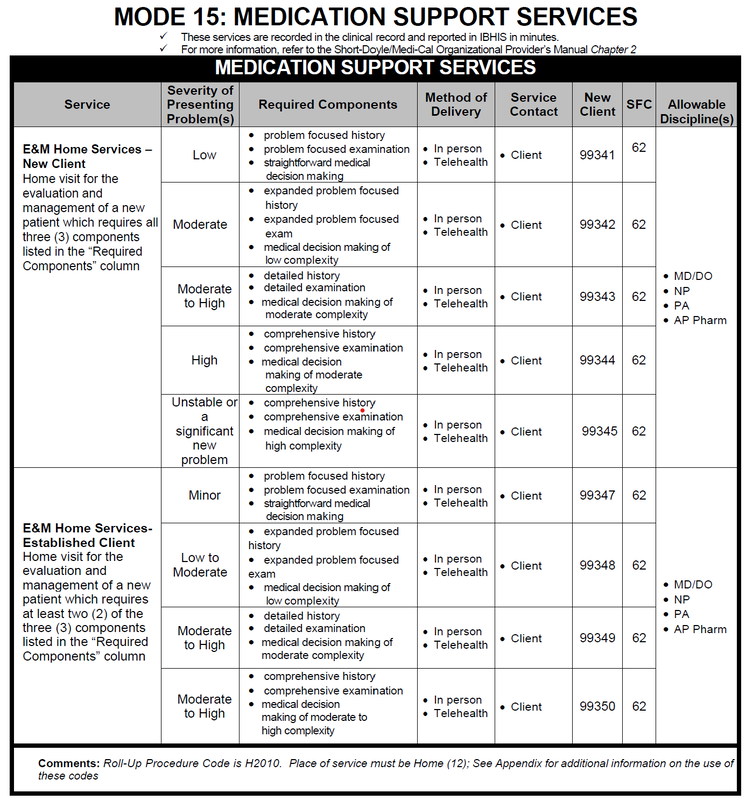

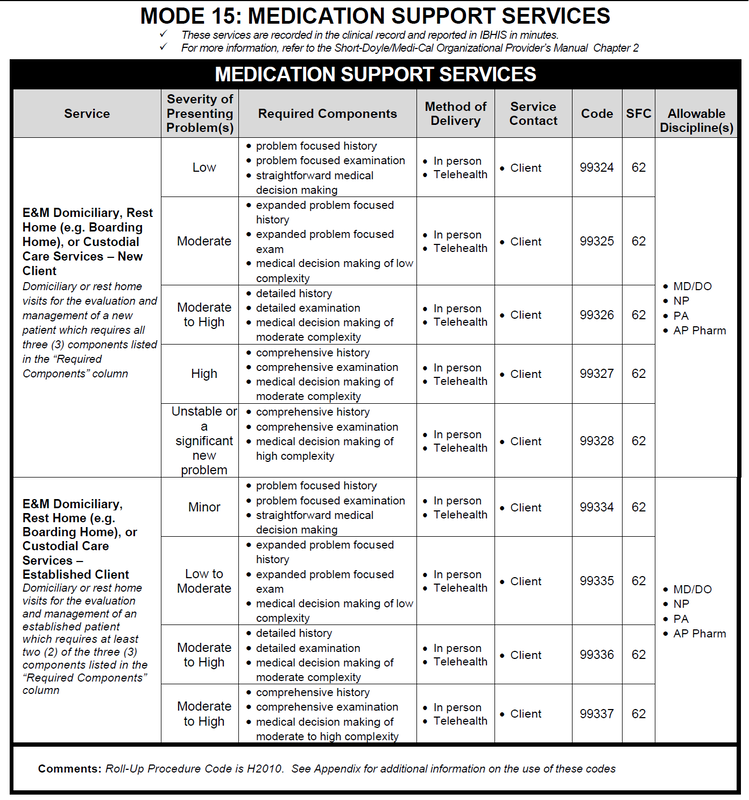

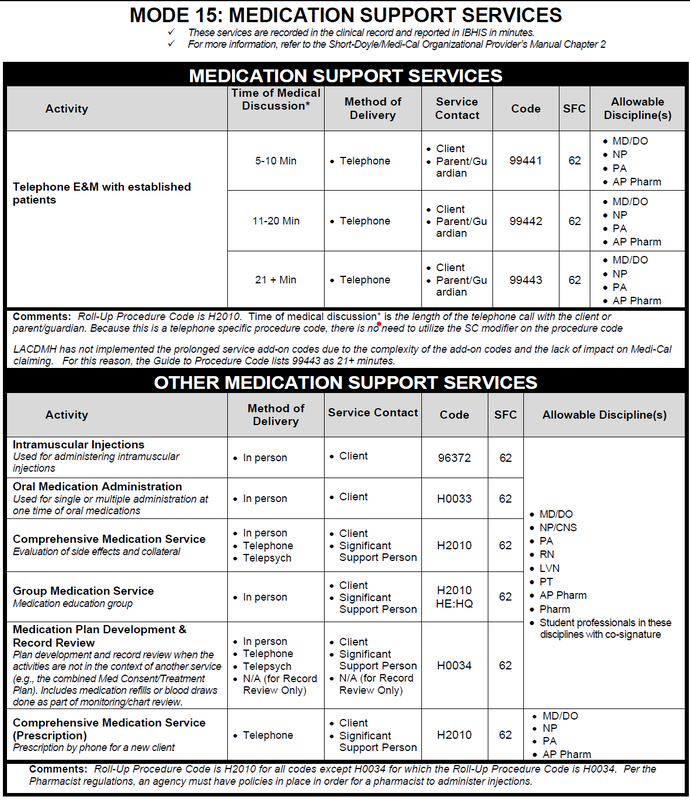

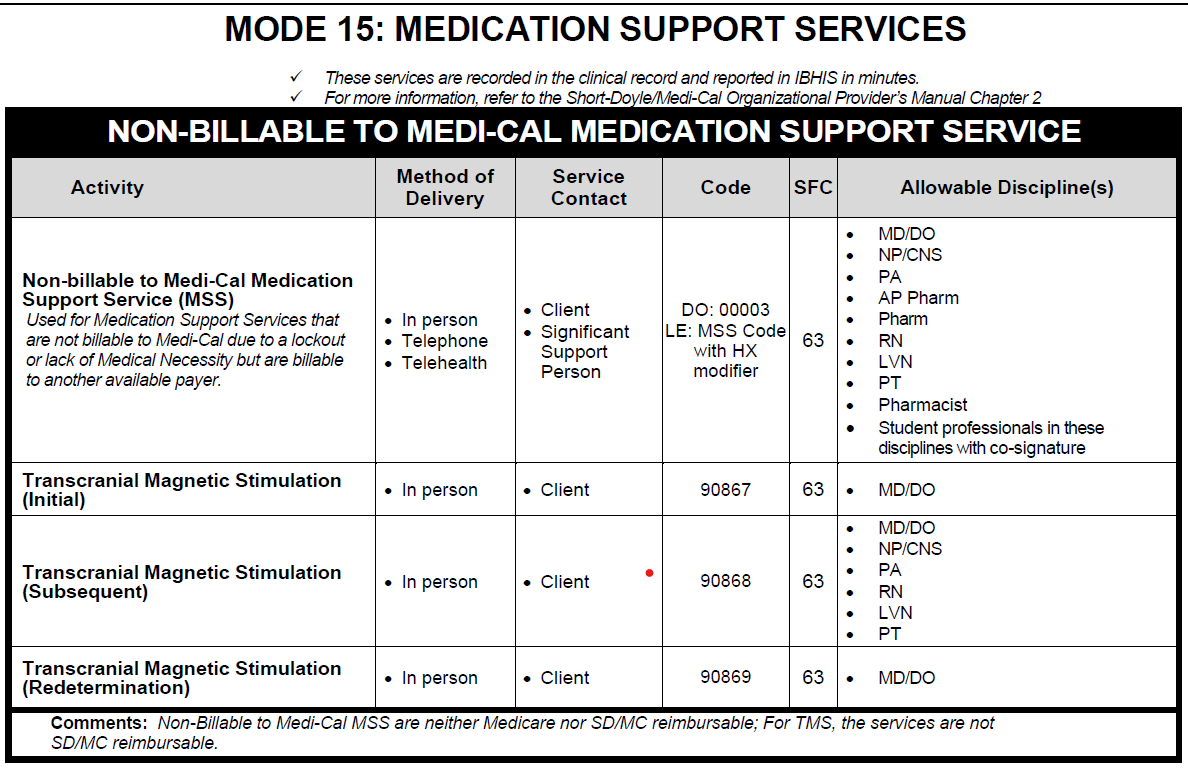

Specialty Mental Health Services – Outpatient and Day Services

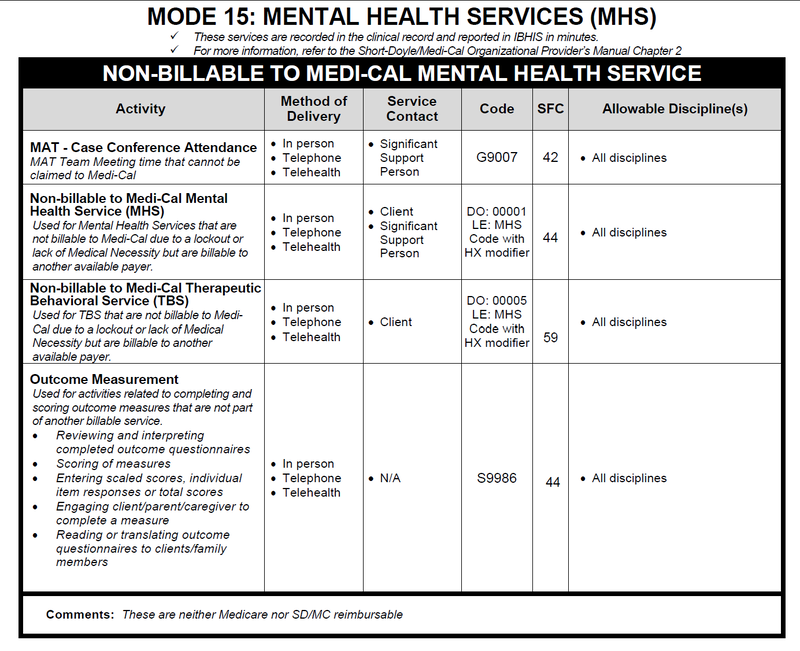

Mental Health Services (Mode 15)

Clinical Assessment with Client

Plan Development

Individual Psychotherapy

Family and Group Services

Rehabilitation

Psychological Testing

Other Mental Health Services

Record Review

No Contact – Report Writing

Services to Special Populations

MAT

Intensive Home Based Services (IHBS)

TBS

Non-Billable to Medi-Cal Mental Health Services

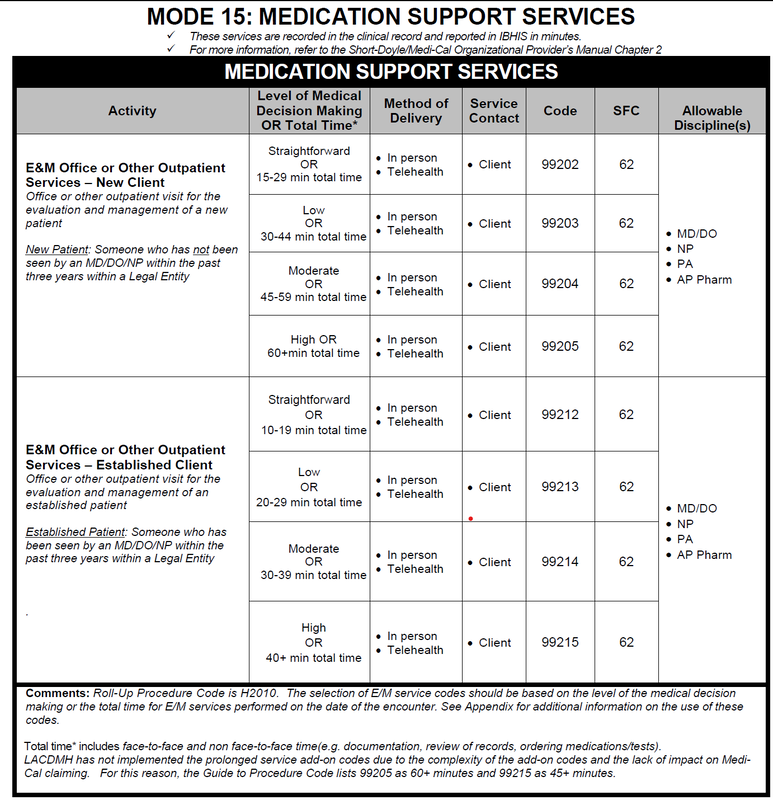

Medication Support Services (Mode 15)

Evaluation & Management

Medication Support

Non-Billable to Medi-Cal Medication Support Services

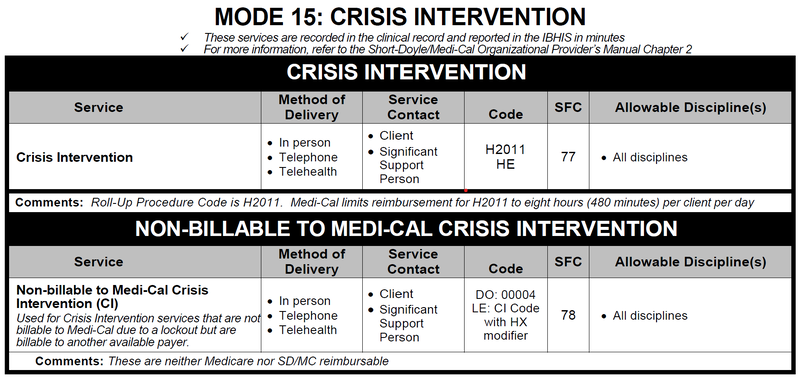

Crisis Intervention (Mode 15)

Crisis Intervention

Non Billable to Medi-Cal Crisis Intervention

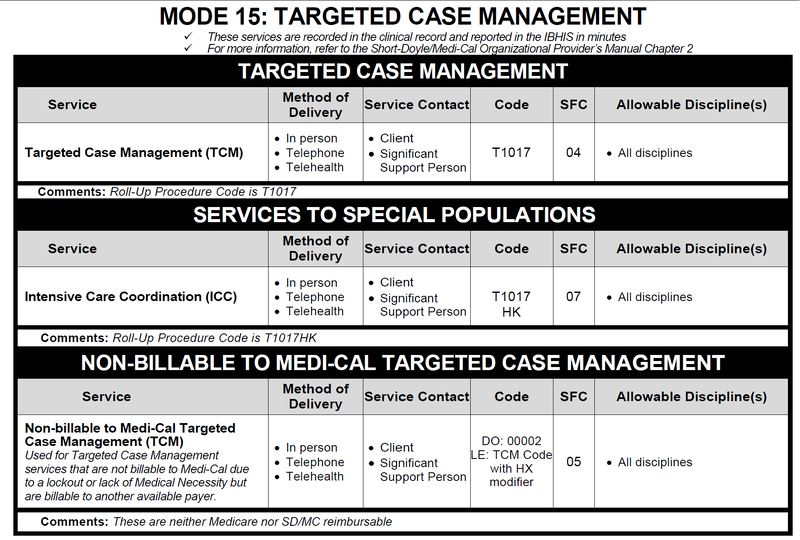

Targeted Case Management (Mode 15)

Targeted Case Management

Services to Special Populations

Intensive Care Coordination (ICC)

Non-Billable to Medi-Cal Targeted Case Management

Crisis Stabilization, Day Rehabilitation and Day Treatment Intensive (Mode 10)

Crisis Stabilization

Day Rehabilitation and Day Treatment Intensive

Non-Medi-Cal Services

Socialization and Vocational Day Services (Mode 10

Community Outreach Services (Mode 45) and Case Management Support (Mode 60)

24-hour Services

Residential & Other Supported Living Services (Mode 05)

State Hospital, IMD, & MH Rehabilitation Center Services (Mode 05)

Acute Inpatient (Mode 05)

Network (Fee-For-Service) (Mode 15)

Electroconvulsive Therapy

Evaluation & Management – Hospital Inpatient Services

Evaluation & Management – Nursing Facility

Evaluation & Management – Domiciliary, Board & Care, or Custodial Care Facility

Evaluation & Management – Office or Other Outpatient Service

Evaluation & Management – Outpatient Consultations

Evaluation & management – Inpatient Consultations

Community Partner (Mode 15)

Comprehensive Community Support

Never Billable Codes in IBHIS

Analiza porównawcza klasyfikacji procedur w USA i Polsce (rozporządzenie koszykowe) DOC

Dokument amerykański daje wyobrażenie, jak powinno wyglądać polskie rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia w sprawie świadczeń gwarantowanych w zakresie opieki psychiatrycznej opracowane do rozliczeń za ich wykonanie.

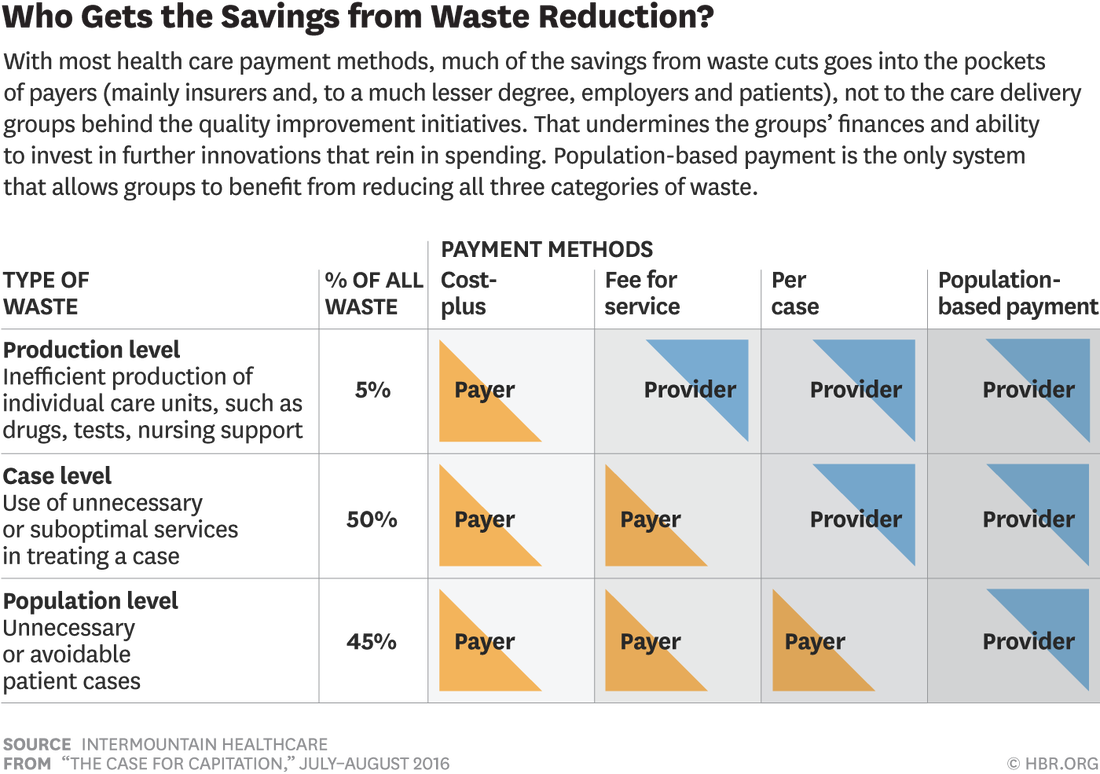

W Polsce i USA funkcjonuje podobny system finansowania ochrony zdrowia psychicznego według zasady „fee-for-service”, czyli refundacja za świadczenie. To jest rozwiązanie typowe dla ubezpieczeń społecznych. W odróżnieniu od Stanów Zjednoczonych w Polsce nie ma wolnego rynku ubezpieczeń zdrowotnych. Stąd wystarczy jedno zarządzenie prezesa NFZ do punktowej wyceny poszczególnych procedur z koszyka. Negocjacjom podlega jedynie stawka, wartość złotówkowa punktu lub osobodoby. Ponieważ w USA funkcjonuje wolny rynek ubezpieczeń zdrowotnych dlatego stworzono ogólnokrajowy katalog procedur z kodami, standardami czasowymi, uprawnione grupy zawodowe do ich wykonywania. Porównanie koszyka polskiego i amerykańskiego pozwala zauważyć pewne różnice, które pociągają za sobą określone konsekwencje.

1. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview /psychiatryczny wywiad diagnostyczny/ może przeprowadzić każdy pracownik zdrowia psychicznego. Jeżeli rozumieć to jako rozmowę o problemach zdrowia psychicznego, z którymi ktoś zgłasza się do CZP na przykład w punkcie zgłoszeniowym, to oczywiste jest, że nie musi to być porada lekarska diagnostyczna lub tylko porada psychologiczna. Każdy profesjonalnie przygotowany do kontaktu terapeutycznego z pacjentem i jego rodziną może taką rozmowę przeprowadzić. W Polsce od początku reformy 1999 roku zawężono kontakt diagnostyczno-terapeutyczny do psychiatry i psychologa /psychoterapeuty/.

2. Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview with Medical Services – diagnostyczny wywiad psychiatryczny ze świadczeniem medycznym jest realizowany wyłącznie dla lekarzy. Tak więc dodanie „czynności medycznych” do wywiadu psychiatrycznego decyduje o wyłączności lekarskiej. To jest lekarska porada diagnostyczna w polskim wydaniu.

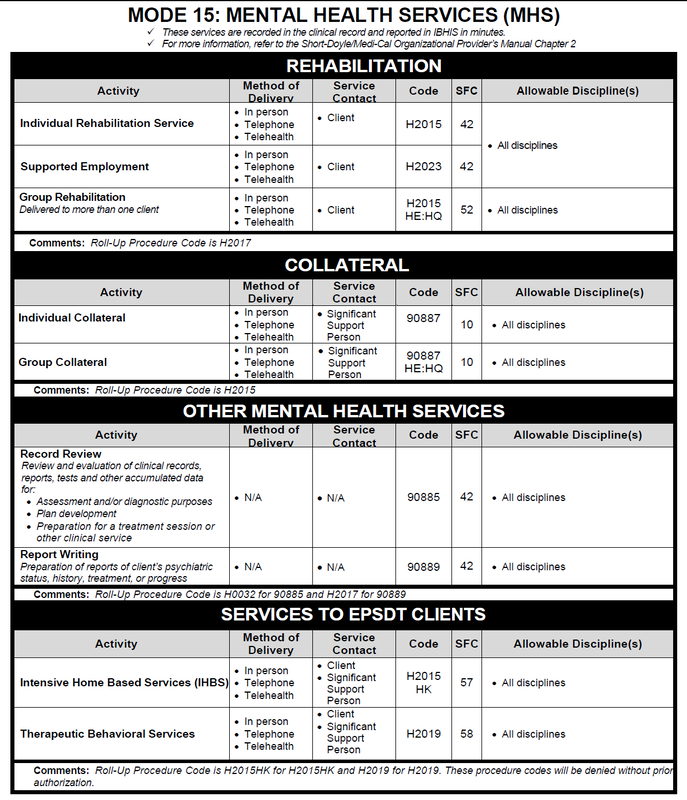

3. Plan Development – Plan Development A stand-alone Mental Health Service that includes developing Client Care Plans, approval of Client Care Plans and/or monitoring of a client’s progress. Plan development may be done as part of an interdisciplinary inter/intra-agency conference and/or consultation with other mental health providers in order to develop and/or monitor the client’s mental health treatment. Plan development may also be done as part of a contact with the client in order to develop and/or monitor the client’s mental health treatment.

Szczegółowy opis pokazuje, że plan terapii /opieki/ tworzony jest zespołowo. Do tego czasami konieczne jest zorganizowanie zebrania zebrania /konferencji, konsultacji przypadku/. Wiadomo, że specjaliści/terapeuci mogą komunikować się ze sobą za pomocą wpisów do dokumentacji medycznej. Jednakże w Polsce rozliczane są wyłącznie porady, wizyty, osobodni z udziałem pacjenta. Wszystkie inne czynności pod nieobecność pacjenta, tak jak zebranie zespołu ustalające plan terapii nie są refundowane. W modelu psychiatrii „mono-dyscyplinarnej” i „gabinetowej” plan terapii (farmakoterapia, psychoterapia) określa jednoosobowo lekarz lub psychoterapeuta. W terapii zaburzeń lękowych, nie psychotycznych, nie upośledzających funkcjonowanie społeczne to jest wystarczające. W polskich realiach nie było warunków do pracy zespołowej niezbędnej w modelu środowiskowym. W podejściu systemowym i otwartego dialogu indywidualny plan terapii/zdrowienia może być omawiany i uzgadniany w obecności pacjenta i jego rodziny. Jednakże powstaje problem, jak taką sesję terapeutyczną rozliczyć, czy jako poradę lekarską diagnostyczną, czy poradę psychologiczną, czy sesję terapii rodzinnej, czy sesję wsparcia psychospołecznego. Jakkolwiek rozliczyć taką procedurę, to w Polsce będzie ona nieopłacalna. Z praktyki wiadomo, że intensywny i wielodyscyplinarny kontakt terapeutyczny od początku kryzysu psychicznego z włączeniem rodziny i innych opiekunów przynosi efekty na dalszym etapie leczenia. Dopiero w pilotażowych Centrach Zdrowia Psychicznego istnieje szansa, że zostaną przywrócone normalne standardy opieki psychiatrycznej.

4. Collateral - Collateral (one or more clients represented) 1) Gathering information from family or significant support person(s) for the purpose of assessment. 2) Interpretation or explanation of results of psychiatric examinations or other accumulated data to family or other significant support person(s) 3)Providing services to family or significant support person(s) for the purpose of assisting the client in his/her mental health treatment (e.g., providing consultation or psychoeducation about client’s condition, teaching the family member or significant support person(s) skills that will improve the client’s mental health condition). 90887** A collateral/significant support person is, in the opinion of the client or the staff providing the service, a person who has or could have a significant role in the successful outcome of treatment, including, but not limited to, parent, spouse, or other relative, legal guardian or representative, or anyone living in the same household as the client. Agency staff, including Board & Care operators, are not collaterals.

Ta procedura nie ma odpowiednika w polskim koszyku, bo dotyczy osób innych niż pacjent, z którymi czasami trzeba się spotkać. Dorosły pacjent raczej powinien uczestniczyć w sesjach rodzinnych i sesjach wsparcia psychospołecznego, jednak nie zawsze to jest możliwe. W psychiatrii wieku rozwojowego takich sytuacji jest więcej, gdy dziecko nie uczestniczy w rozmowie terapeuty z rodzicami, na przykład dla omówienia spraw konfliktowych między nimi itp.

Szczególnie w psychiatrii dzieci i młodzieży – aktualna kategoryzacja procedur i sposób ich sprawozdawania do NFZ zniekształca rzeczywistość i ogranicza działania terapeutyczne. Z uwarunkowań prawnych wiadomo, że dziecko i nastolatek do osiągnięcia pełnoletności jest pacjentem ubezwłasnowolnionym. Rodzice lub opiekunowie prawni muszą wyrazić zgodę na leczenie. Od ukończenia szesnastego roku życia nastolatek co najwyżej może się nie zgodzić na terapię. W praktyce to rodzice najczęściej, prawie zawsze, rejestrują dzieci do psychiatry lub psychologa /psychoterapeuty/, a następnie przyprowadzają je do specjalisty. Lekarz lub psycholog prawie zawsze rozmawia z rodzicem lub rodzicami w trakcie lub po kontakcie z dzieckiem. To powinno być odnotowane w systemie – każdy uczestnik spotkania i opisany każdy kontakt. Dopiero wówczas uda się ocenić w jakich standardach prowadzona jest w Polsce ambulatoryjna opieka psychiatryczna dla dzieci i młodzieży, czemu tak mało jest sesji terapii rodzinnych.

5. Other no contact services -Review of Records Review of Records - Psychiatric evaluation of hospital records, other psychiatric reports, psychometric and/or projective tests, and other accumulated data for: Assessment and/or diagnostic purposes; Plan Development (development of client plans and services and/or monitoring a client’s progress) when not in the context of another service Note: All of these services are classified as Individual Mental Health Services and are reported under Service Function 42; When claiming for Review of Records, there must be clear documentation regarding how the information reviewed will inform the assessment, diagnosis and/or treatment plan.; No contact - Report Writing does not include activities such as writing letters to notify clients that their case will be closed (Przegląd dokumentacji medycznej w celach diagnostycznych oraz układanie lub monitorowanie IPZ)

6. Other no contact services - Report Writing No contact – Report Writing - Preparation of reports of client’s psychiatric status, history, treatment, or progress to other treating staff for care coordination when not part of another service Note: All of these services are classified as Individual Mental Health Services and are reported under Service Function 42; When claiming for Review of Records, there must be clear documentation regarding how the information reviewed will inform the assessment, diagnosis and/or treatment plan.; No contact - Report Writing does not include activities such as writing letters to notify clients that their case will be closed(bez kontaktu z pcjentem - pisanie dokumentacji medycznej)

Punkty 5 i 6 to inne czynności związane z opracowaniem i analizą dokumentacji medycznej. W Polsce nie wyodrębnia się tej czynności, zakładając, że porada zawiera prowadzenie dokumentacji medycznej. Wówczas należy się spodziewać, że specjalista będzie skracał czas kontaktu terapeutycznego z pacjentem w ramach standardu czasowego. W zarządzeniach prezesa NFZ oczywiście jest podane, że porady mają trwać co najmniej określony czas. Formalnie specjalista może poświęcić nieograniczoną ilość czasu, tyle że NFZ zapłaci jedynie za to minimum. W przypadku gdy terapeuta w sprawozdawczości podaje osobno czas kontaktu terapeutycznego i czas na czynności administracyjne możliwe jest dochowanie standardów.

7. Medication support - Comprehensive Medication Service - Medication Support Services to clients, collaterals, and/or other pertinent parties (e.g. PCP). Services may include: Prescription by phone, medication education by phone or in person, discussion of side effects by phone or in person, medication plan development by phone or in person, and medication group in person. /zalecanie i edukacja o lekach także przez telefon/ farmakoterapia jest jednoznacznie skategoryzowana, jako medication support. W dalszych szczegółowych opisach podano, że za edukację dotyczącą zażywania leków odpowiada lekarz, ewentualnie pielęgniarka./

8. Rehabilitation Service - Individual Rehabilitation Service: Service delivered to one client to provide assistance in improving, maintaining, or restoring the client’s functional, daily living, social and leisure, grooming and personal hygiene, or meal preparation skills, or his/her support resources. CCR §1810.243. /Indywidualne świadczenie rehabilitacyjne – kojarzy się z terapią środowiskową/

9. Group Rehabilitation (family and non-family) Service delivered to more than one client at the same time to provide assistance in improving, maintaining, or restoring his/her support resources or his/her functional skills - daily living, social and leisure, grooming and personal hygiene, or meal preparation. /grupowa rehabilitacja kojarzy się z oddziałem dziennym/

10. Rehabilitation Service - Psychoeducation to Non-Client, Non-Collateral Rehabilitation Service - Psychoeducation to Non-Client, Non-Collateral: Providing services to non-clients, non-collaterals (e.g., school teachers) for the purpose of assisting the client in his/her mental health treatment (e.g., providing consultation or psychoeducation about client’s condition, teaching the non-client, non-collateral person skills that will improve the client’s mental health condition).

Psychoedukacja dla pracowników instytucji np. nauczyciele, którzy nie są pacjentami, ani ich bliskimi. Sesja wsparcia psychospołecznego nie odnosi się do takiej sytuacji. W psychiatrii dzieci i młodzieży to jest potrzebna procedura /czynność/, której brakuje w polskim koszyku. W Polsce koszyk został upleciony w paradygmacie medycznym – leczenie to działania lekarza/terapeuty adresowane do pacjenta. W medycynie zabiegowej i somatycznej to się sprawdza. W psychiatrii, gdzie w standardach światowych obowiązuje model bio-psycho-społeczny, taka zawężenie rozumienia świadczeń medycznych/pomocowych wypacza opiekę psychiatryczną.

Należy dodać, że rehabilitacja jest prowadzona przez wszystkich pracowników zdrowia psychicznego.

11. On-going support to maintain employment (This service requires the client be currently employed, paid or unpaid; school is not considered employment.)

Ta procedura wskazuje na obowiązek troski o utrzymanie zatrudnienia przez pacjenta, w okresie gdy jest w opiece psychiatrycznej.

Pełny przegląd amerykańskiego katalogu procedur wskazuje na to, że został on opracowany z myślą skategoryzowania wszelkich niezbędnych czynności związanych z opieką psychiatryczną w różnych formach. Można tam znaleźć wiele innych różnić w stosunku do Polski, które prowokują do zastanowienia, czemu u nas jest właśnie tak, jak jest. Bez oceny, gdzie jest lepiej. Tak po prostu, dla zrozumienia skąd i po co jest to co jest. Amerykańska klasyfikacja procedur /czynności/ sprawia wrażenie, że jest zupełna. Uwzględnia zarówno kontakt twarzą w twarz i za pomocą telefonu, Internetu.

Czy każda procedura jest wyceniona? Tego nie wiem na pewno. To jest do sprawdzenia. Jednak wątpię. Prawdopodobnie wyceniony jest czas pracy danego specjalisty odpowiednio do kwalifikacji. W sprawozdaniu wpisuje się kod danej procedury i określa ile czasu to zajęło. To jest podstawą do rozliczenia usługi.

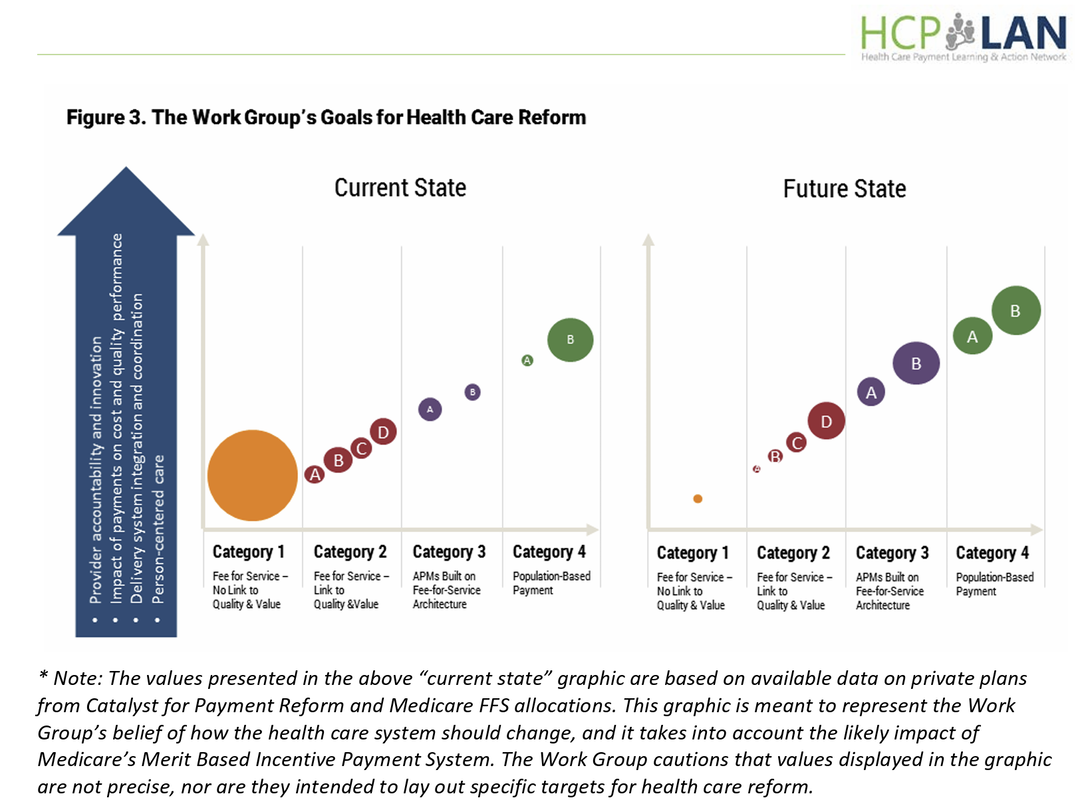

Transforming Mental Health Care in the United States

The U.S. mental health system has reached a moment (2021) when a historic transformation to address persistent problems appears realistic. These problems include high levels of unmet need for care, underdevelopment of community-based supports that can help avoid unnecessary emergency care or police engagement, and disparities in access and quality of services.

Amerykański system zdrowia psychicznego osiągnął moment (2021), w którym nastąpił historyczny transformacja mająca na celu rozwiązanie utrzymujących się problemów wydaje się realistyczna. Problemy te obejmują wysoki poziom niezaspokojonej potrzeby opieki, niedorozwój wsparcia środowiskowego, które może pomóc uniknąć niepotrzebnej opieki w nagłych wypadkach lub zaangażowania policji, a także różnic w dostępie i jakość usług.

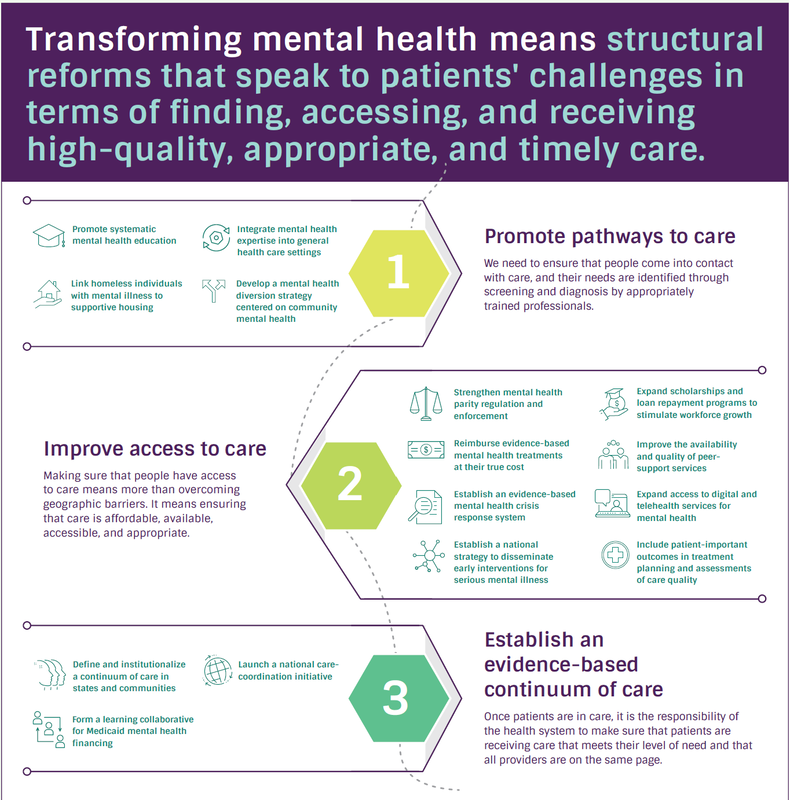

1. Promote pathways to care. Too often, people with mental health needs do not even make contact with mental health providers. This is partly attributable to a system in which individuals are unaware of available resources, fear the repercussions and stigma associated with mental illness, and fail to receive screenings and diagnoses. High-need populations, such as those with a pattern of homelessness or criminal justice involvement, may also require shepherding to services that best meet their needs.

2. Improve access to care. Once a patient is identified as needing care, several barriers may obstruct actual receipt of services. These include the cost to the consumer (affordability), the capacity of the system to provide adequate care in a timely manner (availability), the location

of services (accessibility), and the suitability of services from the consumer’s perspective(appropriateness). All four barriers must be removed for patients to use services.

3. Establish an evidence-based continuum of care. Once patients are inside the system, uncertainty remains. Will the care be evidence-based? Will it correspond to the patient’s level of need? Will it be provided in a timely and consistent manner? There is no guarantee that mental health systems can answer “yes” to these questions and, ultimately, improve patient outcomes. For this to happen, the internal mechanics of systems need to be recalibrated, and rewards need to be established to align services with patient needs.

Tłumaczenie Google

1. Promuj ścieżki opieki. Zbyt często osoby z potrzebami w zakresie zdrowia psychicznego nawet nie kontaktują się z dostawcami usług w zakresie zdrowia psychicznego. Częściowo można to przypisać systemowi, w którym jednostki nie są świadome dostępnych zasobów, obawiają się konsekwencji i piętna związanego z chorobą psychiczną oraz nie poddają się badaniom przesiewowym i diagnozom. Populacje o wysokich potrzebach, takie jak bezdomne lub zaangażowane w wymiar sprawiedliwości w sprawach karnych, mogą również wymagać kierowania do usług, które najlepiej odpowiadają ich potrzebom.

2. Poprawić dostęp do opieki. Gdy pacjent zostanie zidentyfikowany jako wymagający opieki, kilka barier może utrudniać faktyczne otrzymanie usług. Obejmują one koszt dla konsumenta (przystępność cenowa), zdolność systemu do zapewnienia odpowiedniej opieki w odpowiednim czasie (dostępność), lokalizację usług (dostępność) oraz przydatność usług z punktu widzenia konsumenta (właściwość). Wszystkie cztery bariery muszą zostać usunięte, aby pacjenci mogli korzystać z usług.

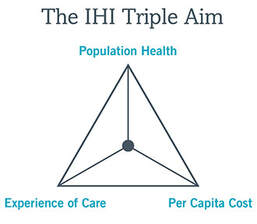

3. Ustanowienie ciągłości opieki opartej na dowodach. Gdy pacjenci znajdą się w systemie, niepewność pozostaje. Czy opieka będzie oparta na dowodach? Czy będzie odpowiadać poziomowi potrzeb pacjenta? Czy będzie świadczona w sposób terminowy i spójny? Nie ma gwarancji, że systemy zdrowia psychicznego mogą odpowiedzieć „tak” na te pytania i ostatecznie poprawić wyniki leczenia pacjentów. Aby tak się stało, wewnętrzna mechanika systemów musi zostać ponownie skalibrowana, a finansowanie musi mieć na celu dostosowanie świadczeń do potrzeb pacjentów.

The U.S. mental health system has reached a moment (2021) when a historic transformation to address persistent problems appears realistic. These problems include high levels of unmet need for care, underdevelopment of community-based supports that can help avoid unnecessary emergency care or police engagement, and disparities in access and quality of services.

Amerykański system zdrowia psychicznego osiągnął moment (2021), w którym nastąpił historyczny transformacja mająca na celu rozwiązanie utrzymujących się problemów wydaje się realistyczna. Problemy te obejmują wysoki poziom niezaspokojonej potrzeby opieki, niedorozwój wsparcia środowiskowego, które może pomóc uniknąć niepotrzebnej opieki w nagłych wypadkach lub zaangażowania policji, a także różnic w dostępie i jakość usług.

1. Promote pathways to care. Too often, people with mental health needs do not even make contact with mental health providers. This is partly attributable to a system in which individuals are unaware of available resources, fear the repercussions and stigma associated with mental illness, and fail to receive screenings and diagnoses. High-need populations, such as those with a pattern of homelessness or criminal justice involvement, may also require shepherding to services that best meet their needs.

2. Improve access to care. Once a patient is identified as needing care, several barriers may obstruct actual receipt of services. These include the cost to the consumer (affordability), the capacity of the system to provide adequate care in a timely manner (availability), the location

of services (accessibility), and the suitability of services from the consumer’s perspective(appropriateness). All four barriers must be removed for patients to use services.

3. Establish an evidence-based continuum of care. Once patients are inside the system, uncertainty remains. Will the care be evidence-based? Will it correspond to the patient’s level of need? Will it be provided in a timely and consistent manner? There is no guarantee that mental health systems can answer “yes” to these questions and, ultimately, improve patient outcomes. For this to happen, the internal mechanics of systems need to be recalibrated, and rewards need to be established to align services with patient needs.

Tłumaczenie Google

1. Promuj ścieżki opieki. Zbyt często osoby z potrzebami w zakresie zdrowia psychicznego nawet nie kontaktują się z dostawcami usług w zakresie zdrowia psychicznego. Częściowo można to przypisać systemowi, w którym jednostki nie są świadome dostępnych zasobów, obawiają się konsekwencji i piętna związanego z chorobą psychiczną oraz nie poddają się badaniom przesiewowym i diagnozom. Populacje o wysokich potrzebach, takie jak bezdomne lub zaangażowane w wymiar sprawiedliwości w sprawach karnych, mogą również wymagać kierowania do usług, które najlepiej odpowiadają ich potrzebom.

2. Poprawić dostęp do opieki. Gdy pacjent zostanie zidentyfikowany jako wymagający opieki, kilka barier może utrudniać faktyczne otrzymanie usług. Obejmują one koszt dla konsumenta (przystępność cenowa), zdolność systemu do zapewnienia odpowiedniej opieki w odpowiednim czasie (dostępność), lokalizację usług (dostępność) oraz przydatność usług z punktu widzenia konsumenta (właściwość). Wszystkie cztery bariery muszą zostać usunięte, aby pacjenci mogli korzystać z usług.